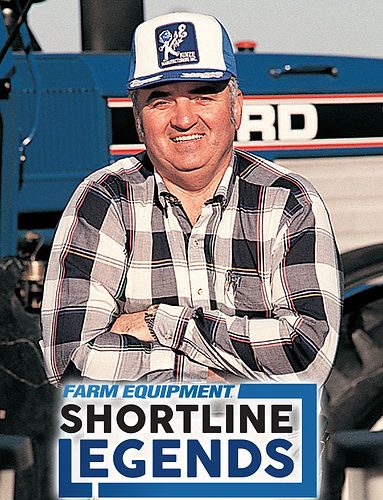

At 21 years old, Jon Kinzenbaw opened a welding shop in 1965 that would eventually become Kinze Manufacturing.

After struggling for almost a decade, Kinzenbaw made his mark with the introduction of the grain cart. Later, his innovative planter design leapfrogged the rest of the industry and propelled the company to one of the largest, privately held agricultural equipment manufacturers in North America. Today, the company has 30 acres of under-roof facilities, over 1 million square feet of manufacturing space and nearly 900 employees worldwide. To put this Iowa manufacturer, located in the 3,000-population town of Williamsburg, Iowa, into perspective, consider these numbers: 7 truckloads of steel delivered each day, laser cutters that automatically process 22,000 pounds of steel each weekend, a powder coat line that’s almost 1 mile long and 40,000 active part numbers to maintain.

And along the way to building the company we know today, Kinzenbaw stood up to Deere — and won.

Welding Shop Origins

“We started in October 1965 getting the building ready for a mid-December opening,” Kinzenbaw recalled during a 2018 podcast with Farm Equipment, adding that he’d borrowed $3,500 for tools and equipment. “A fellow broke a loader frame and begged me to fix it because he needed it for chores the next morning. So, I did a $15 weld job on December 10, and that was the official start. We opened the doors and never had a day we didn’t have something to do.”

The first jobs were repairing farm implements, but that led to overhauling engines and truck and tractor service. Along the way, a niche was discovered in “repowering” John Deere tractors. “We were taking out the 130-horsepower engine and putting in a Detroit Diesel, which is about 300 horse,” Kinzenbaw says. “We could really make a plow move.”

“Jon Kinzenbaw was vindicated. He had risked health and wealth, and he stood alone against Goliath. When Goliath fell, however, it fell with a thud that would have shaken the grave of its founder, John Deere, and shamed the spirit in which he had fought and championed the cause of individual farmers…” – Jim Hill, Kinze Manufacturing Attorney

At the same time, he’d also been doing work for a fertilizer dealer located across the road. A higher horsepower tractor could lead to a quicker way to apply anhydrous ammonia, so he built a pair of large toolbars for that task. “They were 30-foot wide, and we started building the wagons to pull behind them. We had a 2,000-gallon wagon, which was unheard of then. With that kind of horsepower, we could double it. The anhydrous bar was kind of the first innovative product we built, followed by an adjustable width plow in ’71, which I licensed to DMI.”

His first patent was for a high-clearance, variable-width moldboard plow. Other industry-firsts brought to market by Kinzenbaw include: folding row markers, push row units, vacuum-type and brush-type seed meters, hydraulic weight transfer system, bulk air seed delivery system, electrically driven seed meters and a multi-hybrid planter. In total, Kinze has over 100 patents since that first one in 1974.

Grain Cart Pioneer

In the fall of 1971, Kinzenbaw built a wagon for a local farmer to haul corn away from his combine, which spawned another idea. “We pioneered the grain cart concept, which had large, high-flotation tires and unloaded itself in under 3 minutes. It was the ‘go-between’ from the combine to the truck.” He recalls plenty of detractors telling him his concept wasn’t feasible. “But within 5 years, everybody seemed to need one.”

From the get-go, Kinzenbaw attacked inefficiency. “When first building grain carts, I’d build a frame, pull it outside and build another frame. Then, we’d bring them back in and put the axles under them, set the tubs and put the augers in,” he says in the podcast. Realizing that he was wasting a lot of unnecessary man-hours, Kinzenbaw took a cue from Henry Ford.

“I laid a piece of angle iron on the floor with the point up, made clips on it and then I’d bolt that to the floor. We had a steel roller on the hitch of the frame and, on the back, I had a pair of hard rubber tires like you would have on a wagon, for factory rollers. We started winching that through the plant, and we’d hook one behind the other. The steel roller grounded that frame, so it would go past the guy welding who could do his job, and then it’d go on. If he didn’t keep up in getting it down the line, the guys behind him would say, ‘Hurry up, get done.’ That put urgency in the process, and we doubled our production overnight.”

‘Disruptive Innovation.’ In 1975, Kinzenbaw introduced his first “disruptive innovation” to the market — his folding planters.

As planters grew larger to match farmers’ increasing acreage, Kinzenbaw heard friends complaining about time wasted dismantling and loading their planters onto drop-bed trailers. “If it got beyond an 8-row, they loaded it on a trailer and hauled it end-ways,” he remembers.

In his autobiography, Fifty Years of Disruptive Innovation, Kinzenbaw wrote, “there was clearly a need for a planter that a farmer could fold mechanically from the tractor seat, would be narrow enough to drive down the road to the next farm and then mechanically unfold to planting position. Folding and transporting a planter this way took very little time and labor.

“The first planters were designed to accept International Harvester, Allis-Chalmers and John Deere row units. All these companies priced their row units individually for sale through their dealers. After a couple of years, however, 96% of the rear-fold planters were being built with the new John Deere Max Emerge row units. The Max Emerge row unit had several features that were highly desirable: a double disc opener, gauge wheels with depth control, canted closing wheels and the finger pickup meter.”

More on Jon Kinzenbaw & the Kinze Story

Read more on Jon Kinzenbaw and Kinze’s contribution to the farm equipment industry:

- Kinze Manufacturing’s Long Road to ‘Disruptive Innovation’ in the Farm Equipment Industry

- The Rear-Fold Planter and the Battle that Ensued

- [Podcast] Conversations with Ag Equipment’s Entrepreneurs: Kinze's Jon Kinzenbaw and Susie Kinzenbaw Veatch

- [Video] Inside Kinze’s Manufacturing Facility

- Video: Kinze Innovation Center

Kinzenbaw writes that Kinze started buying the Deere row units by the dozens, “and John Deere was happy to sell them to us.”

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, John Deere management and engineers would often stop by Kinzenbaw’s shop in Ladora, Iowa, while traveling between Waterloo and Moline. “They observed me building Big Blue [a 600+ horsepower tractor with a 12-bottom adjustable-width plow] and watched me manufacture my rear-fold planters. They even encouraged me to paint my planter frame green to match the row units,” he says.

Kinze’s rear folding planter toolbar was released in 1975, and to meet the fast-growing demand, Kinzenbaw purchased 10 acres of land and built a new manufacturing plant in Williamsburg.

Battle with Deere

The arrangement was working out well, Kinzenbaw writes, until Deere offered to pay him a royalty on his folding planter design. Deere also wanted him to build a prototype planter incorporating Deere ideas and suggestions. “Some of its managers took me out to lunch at the Veeley Restaurant in Moline and offered me $25 per folding bar. Well, that didn’t sound like much for a planter that was selling for $20,000-$30,000. So I asked them for $100, but they said they couldn’t pay such an ‘exorbitant’ rate,” he writes.

Shortly thereafter, in the spring of 1977, there was reportedly a “tremendous shortage” of the row units. Kinzenbaw went to visit the Deere dealer in Grinnell, Iowa, where he’d been buying some of the row units. The dealership was having trouble getting the 25 row units he had ordered and learned of the cancellation order by the OEM.

Kinzenbaw’s lawyer, Jim Hill, told him what Deere was doing — shutting off Kinze’s supply of row units — was a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. “Deere was forcing customers to buy an undesirable planter toolbar in order to get the highly desired row units. It was becoming obvious that things were not going to improve for the next season, so in the summer of ’77, we filed a lawsuit against Deere in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, based on the antitrust violations and contrived shortages. This was a stern reminder to Deere, and we bandied it through the court system for several months,” Kinzenbaw writes.

It took 3 years to get the battle into court in 1983, and then the judge ordered that two cases — the antitrust suit and Deere’s suit against Kinze for patent infringement — be tried together.

Ultimately, Kinzenbaw won, and in the process he also developed his own row units and no longer relied on competitors for components.

In addition, the easy-to-transport planter excited dealers as the units could essentially be shipped field-ready, without assembly. “We saved dealers a lot of money and then they’d also be eager to sell it because he wouldn’t need to spend 3 weeks’ work putting it together. A big planter that was 60 feet wide and had 47 rows on it,could be delivered on one load, all assembled. That was unheard of 20 years ago.”

Move to Autonomy

In July 2009, Kinze took its grain cart to the next level with the introduction of the autonomous grain cart during its dealer meeting. The autonomous grain cart system allows an unmanned tractor to accompany a combine through the field during harvest. Kinze partnered with Jaybridge Robotics of Cambridge, Mass., to develop the autonomy software to test the system.

Today, the company is led by his daughter, Susie Veatch, though Kinzenbaw is regularly seen on the shop floor.

Nominate a Future Shortline Legends Hall of Famer

Submit a nomination for the next class! The Shortline Legends Hall of Fame recognizes the achievements of individuals who advanced the innovations and success in shortline/independent equipment innovations.