Special to Farm Equipment

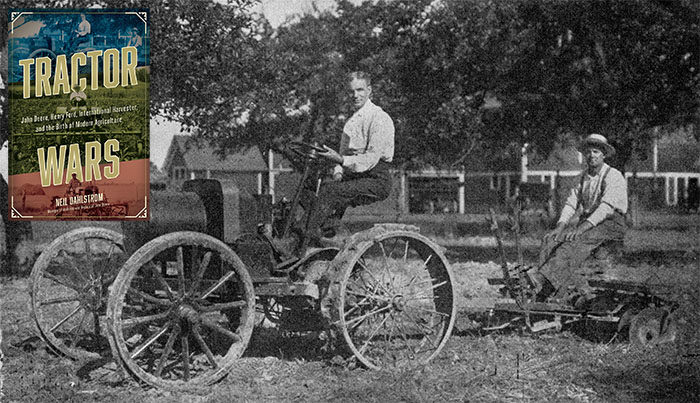

Editor’s Note: Below is a chapter of Neil Dahlstrom’s 2022 book release, Tractor Wars, for which Farm Equipment received special permission to share with you. Dahlstrom is the manager of Archives & History at John Deere, and you may recall our video series with him based on our day spent with him at the John Deere Archives in East Moline, Ill., in 2019 for a special search by my dad, Frank, and me.

Through that quest, we concluded that that often-cited Farm Implement News was part of the Implement & Tractor legacy brand that our company, Lessiter Media, acquired in 2015. The Henry Ford story below is also of personal interest to our family’s centennial farm in Michigan. My dad, Frank, wrote 2 chapters in his 1997 book, Centennial Farm Book, on their “Ford connection.”

Dad’s “Old Tractors Going Strong” chapter examined the Ford tractors on the farm, while “When Henry Ford Didn’t Have the Bucks” covers a didn’t-end-so-well interaction with Henry Ford in 1902. In the latter, the Lessiter family recalls the time would-be bull buyer Henry Ford sped off our property in his still-struggling experimental Model A, insulted that my great-grandfather refused to accept a check on the Shorthorn bull Ford wanted. Ford never returned to our farm. – Mike Lessiter, Editor/Publisher, Farm Equipment magazine

Working from sunup to sundown in the mild cold, the harsh wind, the driving rain, or whatever weather surprises Poor Richard’s Almanack tried its best to predict, Irish immigrant William Ford and his family worked to finish the harvest on their modest acreage in Dearborn, Michigan, outside of Detroit. The scene was repeated by millions of families each year across the country.

The farm offered an honest living to those willing to work for it. The consequences of each day were on exhibit at each meal, often taken in the field. Success was marked daily by a well-nourished, or angrily empty, stomach.

Henry Ford, William’s son, was twelve years old when a new sound captured his imagination. In 1875, the young man and his father crossed paths with a curious contraption on four wheels, sitting lifeless on the long-worn dirt road it had been traveling just outside of Detroit. Writing nearly fifty years later, Ford remembered “that engine as though I had seen it only yesterday, for it was the first vehicle other than horse-drawn that I had ever seen.”

The steam engine, which he learned was made by Nichols, Shepard & Company of Battle Creek, Michigan, had a chain drive between the engine and its two rear wheels. “It was intended to drive threshing machines and power sawmills and was simply a portable engine and a boiler mounted on wheels,” Ford later described, reminiscing about his long, inquisitive conversation with the engineer.

Drudgery an Obstacle to Farming’s Potential

Henry Ford, a young man with demonstrated mechanical aptitude, limitless imagination, and ambition, left the farm at the age of sixteen for the city of Detroit. But in reality, he never really left. Nor could he escape the memories, sounds, and cycles of the farm, or what confounded him the most, the too easily accepted traditions of inefficiency and “drudgery,” as he called it, that kept American farmers from realizing their potential.

In time, as Americans developed an appetite for the automobile, Henry Ford directed his talents toward its advancement. The Model T debuted in October 1908, irreversibly accelerating American mobility and culture.

Less than a month later, Ford submitted a short note to the editors of the Farm Implement News, a leading farm journal published in Chicago. Attached was a photo of himself at the wheel of an experimental vehicle assembled from discarded automobile and farm implement parts. While Americans raced to the nearest Ford dealer to buy the people’s car, its creator retreated to the farm to finish the work he had been dreaming about since that fateful encounter at the age of twelve.

He was not alone.

From barns, sheds, machine shops, and factories in Illinois, Minnesota, Michigan, and California, to the endless Canadian prairies and rolling farm fields of North Dakota, the race to revolutionize American agriculture had already begun. The machine was called a tractor.

The Ford Tractor

Henry Ford’s Model T was, in his mind, perfection. In the decades after its debut, few Americans disagreed. Still, the Model T was only part of Ford’s vision for the new American century. Well before he began to think about transportation, the man who by 1913 was building half of the automobiles sold in the United States “had the idea of making some kind of a light steam car that would take the place of horses—more especially, however, as a tractor to attend to the excessively hard labour of ploughing.”

Ford’s relentless pursuit of the farm tractor was driven by his mechanical abilities, a growing nostalgia for his family’s homestead, and a mixed empathy and contempt for farmers, who he thought were unprepared for the technological revolution before them. “From the beginning, I never could work up much interest in the labour of farming,” he wrote. But solving the centuries-old struggle to make the farm efficient was certainly worthy of his attention.

For Farm Equipment Dealers & Manufacturers:

“Tractor Wars is very much an origins story,” Dahlstrom tells Farm Equipment. “It reveals how some of our favorite farm brands and equipment came into existence, and the circumstances and risks that saw some brands survive while others disappeared. It challenges long-held myths and, I hope, introduces new, everyday heroes.

“My favorite part of the book are the rich stories, all of which are built around people, their relationships, their dreams, ambitions, and responses to adversity. Ultimately, this story and its impact on our lives still today has been overlooked for too long.”

The book is available for purchase here.

Soon after his first encounter with a steam engine, Ford was crawling across railroad yards to watch the steam-belching locomotives up close, seeking to understand the complex relationship between size and power. As his understanding of mechanical power grew, so too did his disdain for human inefficiency and wasted labor. His sister, Margaret, said he “wanted things done with the least loss of time and energy. If a job could be done more simply that was the way it should be done.”

Ford continued to fine-tune his mechanical abilities under the daily direction of his father, William, and benefited from the well-equipped workshop on the family farm. William had a taste for technology as well. In 1876, he was one of the nearly ten million people drawn to the Centennial Exposition, the first World’s Fair held in the United States, on the grounds of Fairmont Park in Philadelphia. There, “never before in the history of mankind have the civilized nations contributed such a display of their peculiar treasures,” offered a souvenir publication. William enthusiastically watched “scheduled tests of the steam plows and road engines,” the portable steam engines of the Ames Iron Works, Oswego, New York, or a Bigelow Stationary Engine of the type installed in growing numbers in factories across the country. Margaret remembered her father and his friends talking about “the mechanical exhibits and the wonderful things that could be accomplished by steam power.”

Not long after, Henry found employment as an apprentice at a small machine shop in Detroit, then began working on steam engines at the Detroit Dry Dock Company, steamship builders located at Atwater and Orleans Street. One of its owners would later become one of Ford’s earliest investors. In the fall, Henry returned home to help bring in the harvest.

The Fords were a common, self-sustaining farm family. Henry and his siblings fed and cared for the animals, fetched water, helped with the cooking and cleaning, and joined in the monotonous manual labor that defined each day. He grew increasingly impatient with its operation over time. He vividly remembered his father buying a harvester, a horse-drawn implement that cut grain, in 1881 and, years later, as an adult, was bewildered that so little advancement had been made on the basic machine form. Everything was still done by hand, he later wrote, and should be replaced by machinery.

“Power-farming is simply taking the burden from flesh and blood and putting it on steel,” he rationalized. “The farmer makes too complex an affair out of his daily work,” he penned in My Life and Times, an autobiographical manifesto of his methods and motivations written after the world had crowned him the “flivver king,” a reference to his cheap automobile. “Power is utilized to the least possible degree. Not only is everything done by hand, but seldom is a thought given to logical arrangement. A farmer doing his chores will walk up and down a rickety ladder a dozen times. He will carry water for years instead of putting in a few lengths of pipe. His whole idea, when there is extra work to do, is to hire extra men. He thinks of putting money into improvements as an expense.” To Ford, the waste of farm inefficiency led to wasted effort, high prices, and low profits.

“Nothing could be more inexcusable than the average farmer, his wife, and their children drudging from early morning until late at night,” he wrote from years of experience.

Author’s Comment to Farm Equipment:

“The Model T became a fast sensation due to its simplicity and affordability,” Dahlstrom tells Farm Equipment. “From the Ford Motor Company’s automobile profits, Henry Ford began buying farmland across the state, beginning with a tract of land near his boyhood home in 1909, the first full year of Model T sales. He began restoration of his birthplace, including extant farm buildings, ten years later. The farm was a place of nostalgia, but also a source of creativity and innovation as experimental work on the Fordson, as well as new implements, crop practices, and more, continued.”

A Return to the Farm

Ford eventually used some of his profits to purchase the Ford family homestead outside of Detroit. It became a source of inspiration, a quiet and familiar retreat from the relentless pounding, drilling, and hammering of the automobile factory in constant motion. The family farm also reminded him of the inefficiencies and “drudgery” that drove him away.

In the United States, the average turn-of-the-century farm was smaller than fifty acres, much too small for the impressive steam traction engines more familiar to farmers on the expansive prairies of the American West. Steam was more efficient, but dangerous. Boilers took hours to heat, building pressure that had to be regulated at all times to prevent violent and sometimes catastrophic explosions. Fireboxes were fed highly combustible material, typically wood or straw, on wide-open, wind-blown prairies.

Gasoline was less efficient and harder to obtain, but much more predictable than alternatives. Smaller, portable engines fueled by gasoline or less expensive kerosene were becoming a more common power source for tasks on the farm, and a few manufacturers were offering gasoline traction engines, or tractors, to replace steam traction engines on large western farms.

Early twentieth-century threshing scene in North Dakota. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-40414.

Tractors were used for belt work or drawbar work. A pulley, connected to the flywheel, could be connected by a leather belt to another machine, transfer- ring power from one to the other. The drawbar was a simple horizontal bar at the rear for attaching an implement, most commonly a plow. Tractors were hard to turn, required fuel that cost more than animal feed, and were built with hundreds of custom parts, which were themselves scarce. Parts, and the mechanics to install or repair them, took a long time to secure. And the most reliable, economical form of farm power was still in active service. No farm tractor yet could match the versatility or reliability of the horse.

Ford, surrounded by small farms, had another idea. In 1906, two years before the debut of the Model T, he directed one of his engineers, Joseph Galamb, to assemble a rudimentary tractor built mostly from leftover automobile parts. It had four spoked wheels, was powered by a Model B automobile engine, and had a large, cylindrical water tank mounted on the frame, ahead of the steering wheel and between the two front wheels. A 1907 experiment took the form of what Ford called an “automobile plow,” built with a 24-horsepower, four-cylinder engine and planetary transmission taken from a Ford Model B. The rear wheels came from a grain binder, with the front wheels, axle, steering, and radiator from the Model K.

Ford’s concept was reinforced at a series of farm equipment demonstrations. To increase lagging attendance at a local fair in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, in 1908, organizers decided to hold a tractor contest. It was met with an unexpectedly positive response. Over the next few years, trials evolved from a loosely organized demonstration into a must-attend event for top agricultural equipment manufacturers. For the first time, farmers could see both steam engines and gasoline tractors in action, the likes of which they had only read about. And they could talk to their designers and learn about potential applications on the farm. It was not the event’s intent, but the demonstrations made it increasingly clear that the steam engine era was coming to a close.

Henry Ford sent the Farm Implement News (later morphing into Implement & Tractor and acquired by Farm Equipment in 2015) this photo of an early experimental tractor built from automobile and farm equipment parts, 1908.

The annual demonstrations in Winnipeg further convinced Ford of the value of a small, gasoline tractor as a means to rid the farm of the drudgery and inefficiency that plagued him as a youth on the family farm. In Winnipeg, he saw huge, steam-belching engines mired in the mud, while their smaller, nimbler counterparts demonstrated easy maneuverability and greater efficiency.

In October 1908, as the Model T began to emerge from the Ford factory, Henry Ford, a still relatively unknown local automobile manufacturer, submitted an article and photo to the Farm Implement News, a leading farm journal printed in Chicago. It was published on November 15.

“Ford’s Farm Tractor. One of the automobile concerns which is experimenting in the line of farm tractors is Ford Motor Company, of Detroit, Mich., whose president, Henry Ford, is said to be quite enthusiastic over the subject. The accompanying illustration is a reproduction of a photograph recently taken of Mr. Ford’s farm. It shows one of the company’s experimental farm motors drawing a disk harrow. The driver of the tractor is Mr. Ford.”

For now, the only thing keeping Henry Ford from his farm tractor was the resounding success of the Model T.

Author’s Comment to Farm Equipment:

“Not to give away the ending, but Ford was not gone from the agricultural equipment business for long,” Dahlstrom tells Farm Equipment. “Fordson tractors, built in Cork, Ireland, soon began to reappear in the United States. Production was transferred to Dagenham, United Kingdom, in 1933."

In partnership with Harry Ferguson, the Ford N debuted in the United States in 1939, featuring Ferguson’s three-point hitch. A new era in Ford tractors had started. In the early 1960s, the American and British tractor operations were consolidated under a worldwide brand, which expanded in the 1980s with acquisition of Sperry-New Holland and a few years later, Versatile. But the investments were short-lived. In a move to consolidate its core automotive businesses, Ford sold its tractor operation to Fiat in 1991. Under the arrangement, New Holland was allowed to use Ford branding for a limited time, which it did until 1999. Today, the shadow of the Ford tractor legacy remains in the blue on New Holland tractors (which has gone through several shades and colors).