An operation that feeds 1,500 cattle twice a day in addition to farming nearly 2,500 acres means daily responsibilities leave little “downtime” for long-term planning. However, one father and son team sets aside time and seeks counsel each December to plan for a more efficient and profitable future. A recent long-term planning session involved analyzing the benefits of a deep bedded cattle barn.

The team has been meeting for the past 15 years with Maurice (Moe) Russell of Russell Consulting Group, Panora, Iowa. Russell helps the producers evaluate the previous year’s performance and set projections for the coming year. The producers sought his input on the financial feasibility of a plan to build a deep bedded cattle barn to replace an open lot. The goal was to address the environmental impact of their cattle feeding operation and gain feed conversion efficiencies.

Case Study Scenario

The producers, with the help of one employee, farm 1,200 acres of corn, 1,000 acres of soybeans and 260 acres of oats and hay. One-third of the acres are owned and two-thirds are cash rented. All of the corn is fed to the cattle or chopped for silage and about half of the hay and oats production are fed to the cattle and the remainder is sold.

Operation at a Glance

Location: Iowa

Operation: Corn, soybeans, hay, oats as well as a feedlot operation

Total Acres: 2,460

Total Cattle: 1,500

Employees: 3

Average Annual Revenue: $3,000,000

The 1,500 head of cattle were housed in two separate and adjacent facilities — about half were fed in open front lots and the manure run-off was contained through a berm and pond structure. The other half were fed in open lots with no containment for the manure.

Iowa’s Department of Natural Resources regularly inspects operations that house more than 1,000 head of livestock. The inspectors indicated to the producers that regulations may soon be changing. For instance, facilities that housed more than 300 head would be subject to inspections and manure containment regulations may become more stringent.

“The challenge this farmer had was from an environmental standpoint. He needed to do something with the outside lots and he wanted to improve feed efficiency, rate of gain and animal comfort. He also wanted to build the operation so it would be sustainable for the long run, so he could transition it to his son,” Russell says.

Feed efficiency, environmental benefits and regulatory compliance are three drivers that have equal importance if producers are considering a move to a deep bedded cattle barn. “If cattle feeders don’t do this voluntarily, they are soon going to be fined or forced to do so by regulators,” he says.

You May Also Be Interested In...

Case Study: What is Needed in Developing a Plan for Capital Expenditures?

Understanding your equipment capital expenditure strategy is critical in helping you define your sales and marketing approach. This simple formula tells you when your customers plan to buy equipment.

Russell had consulted with other livestock operators who needed to address similar concerns. “I’ve had other customers who have built deep bedded cattle barns, so I was aware of the opportunities for improved efficiencies and correcting environmental problems,” Russell says. This previous experience is why the team turned to Russell for an analysis of his operation.

Changing Regulations

Beth Doran, Iowa State University Extension and Outreach beef program specialist, says monoslope barns have been in use in some areas of Iowa for about 15 years, while other states are just incorporating the design.

Controlling manure runoff is one of the main reasons they are being utilized. “In Iowa, if a confinement operation has 500 head of cattle or more, it cannot have any discharge,” says Doran, referring to guidelines from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (IDNR).

“Some are using the buildings because of animal comfort in summer and winter. In summertime, it’s the protection from solar radiation and in the wintertime, it’s for protection from bitterly cold winds and snow.

“Some producers claim improved animal performance, but research has demonstrated that most of this improvement has been in periods of inclement weather and tends to be dependent on the season,” Doran says. She lists decreased animal sickness and increased manure value as other key reasons why monoslope barn designs are implemented. The barns are typically designed to accommodate 40-50 square feet per head.

Doran says that, currently, beef cattle operations with 1,000 head or more need to comply with rules defined in the Clean Water Act and obtain the necessary permits. That’s changing, though.

“The Iowa DNR is in the process, over the next 5 years, of inspecting 8,600 large (1,000 head or more) and medium-sized (300-999 head of cattle) facilities to make sure they are compliant and have no run-off issues. They might be looking at GIS (Global Information Systems) maps and if they don’t see a problem, they might just do a ‘desktop assessment.’ If they’re not sure, they might do an on-site visual inspection,” she says.

Monoslope and other cattle barns offer advantages regarding manure run-off and animal health and comfort, but Doran says producers need to factor in any bedding costs and the extra labor to maintain the bedding.

“Whatever facility a producer puts into place, it takes good management to make it work,” she says. Doran and other Iowa State University experts have conducted extensive research on monoslope beef barns. For more information, go to http://tinyurl.com/na44h34/

Professional Consultant’s View

Russell used what he calls a “red light, yellow light, green light” feasibility analysis using working capital figures (current assets minus current liabilities) to determine if the producers were able to support the $800,000 investment for the 120 x 488 foot facility. A red light indicates a risky investment; yellow indicates caution; and green indicates a good investment. “Working capital is the first and most important of the seven indicators. Working capital is the first ‘shock absorber’ to get the operation through financial bumps in the road.

3 Homework Questions

Maurice (Moe) Russell, of Russell Consulting Group based in Panora, Iowa, says if he was a producer looking at the benefits of a deep bedded cattle barn, three of the most important questions he would pose include:

1. Are the improved feed efficiency numbers consistent with others types of buildings, such as deep pit and hoop buildings?

2. Are there any labor savings with the facility or is it similar?

3. What is the expected life of the facility?

Click here for the expert’s responses to these three questions.

“Red light means that working capital is less than 20% of annual expenses. A dollar amount of working capital between 20-50% of annual expenses is a yellow light. A dollar amount of working capital that is greater than 50% is a green light.

“I considered the impact of the expenditure on their overall financial condition and they are very strong financially, so I had no concerns,” Russell says. “I’ve worked with them for many years. I was confident that if they moved forward, it would not put their financial position in a more than normal risk position.”

The other indicators Russell uses when consulting with clients include owner’s equity, return on assets, return on equity, expense/revenue ratio, debt coverage ratio and withdrawals/revenue.

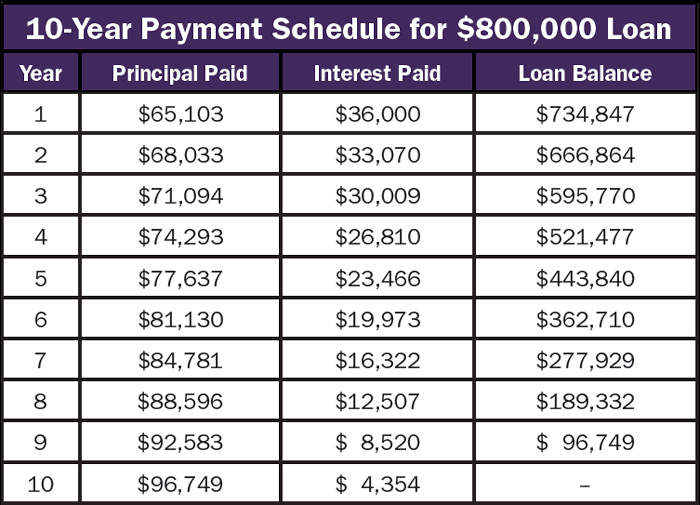

The $800,000 investment for the facility included site preparation, pens and feed bunks. Payments were amortized over 10 years with an even payment of $101,103. (See the table on this page for a breakdown of the payment schedule.) Russell says the 10-year payoff is typical for livestock facilities. “Their farm was used as collateral for the loan. They have a long-standing relationship with their lender.”

Currently, new facilities that house 1,000 or more head of cattle need to be approved by the Iowa DNR, so the producers did not need a permit to build this 750-head facility. It was built on land adjacent to their open lots and there were no issues related to residents or neighboring operations. The open lot without containment was taken out of use after the facility was built.

Configuring the Building

The building (120 x 488 feet) includes four lots, each 80 x 102 feet. It also has an 80-foot area with a chute facility at the end of the building for working cattle. “The typical deep bedded cattle barn is a monoslope design, with a metal roof that is higher on the southern end and lower on the northern end. The doors swing open to the north, letting in the summer breeze to cool the cattle. The doors are closed in the winter,” Russell says.

Payments were amortized over 10 years.

For this operation, chopped corn stalks are baled and then spread for the bedding as needed. Previously, the stalks had no use. The bedding is deepest in the center, at about 4 feet. “There are feed bunks on the north and south side of the building and the cattle work the bedding to both sides when they go to the bunks. Bedding is added to the center of the facility when it gets worked down,” Russell says.

Cattle weigh about 600-750 pounds when they enter the facility and are sold at 1,300-1,500 pounds. The feed consists of corn and dried distillers grains and is fed to the cattle in the barn and in the open lot. The building is cleaned out about once a week and, depending on the season, the manure is spread on fields or piled for later use.

Improving Operating Efficiencies

To analyze gains in feed efficiencies, Russell used data obtained from other clients who were operating similar deep bedding facilities. He also added in manure values based on a University of Minnesota study conducted by Alfred DiCostanzo and Nicole Kennedy-Rambo.

It was projected that the 750 head facility would be full for 340 days per year, allowing 25 days for manure cleanout or other maintenance. Other estimates and projections for feed, gains and manure value were as follows:

“If cattle feeders don’t do this voluntarily they are soon going to be fined or forced to do so by regulators…”

- $0.70 cost of feed per pound of gain

- 3.3 pounds of gain per day

- Feed efficiency to improve by 20% due to animal comfort

- 6 pounds of feed as compared with the 7.5 pounds of feed previously required per pound of gain (based on a dry matter basis).

“Russell Consulting Group customers have realized even better than that in deep bedded buildings over outside lots,” Russell says.

Russell also projected the additional economic gain because the manure collected in the buildings would not contain dirt, as it did in the outside lots. He estimated the manure value of $50 per animal for a deep bedded facility compared with $30 per animal in an outside lot.

Figuring Cost Savings

Based on these estimates, Russell provided the following cost savings analysis for feed:

- $0.70 cost of feed x 3.3 pound gain = $2.31 per day feed cost

- A 20% improvement equals a savings of $0.46 per day

- 340 days of facility use = $157.08 annual savings in feed cost per head

- $157.08 x 750 head = $117,810 in annual savings in feed cost

- The added manure value projection of $15,000 ($20 x 750 head per year) was also figured into the analysis.

Total annual added value: $132, 810 ($117,810 + $15,000)

Loan: $101,103

Net gain: $31,707 or 31% return on investment

“In addition, I have not placed a value on the environmental advantages. The analysis, based on these assumptions, indicated that this was a good investment,” Russell says. “The results are even better than what I projected.”

Realizing Other Benefits

Meet the Expert

Maurice (Moe) Russell

Russell Consulting Group

Panora, Iowa

515-480-6711

mrussell@netins.net

Maurice Russell is the cofounder and president of Russell Consulting Group of Panora, Iowa. He is a leading provider of marketing and financial advice to crop and livestock producers. Prior to starting Russell Consulting, he spent 26 years with Farm Credit Services and served as division president, branch lending, where he was responsible for 82 lending offices in Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota and Wyoming. He is also on the faculty of “The Executive Program for Agricultural Producers” (TEPAP) at Texas A&M University.

Based on his experiences and validation from objective sources, Russell was confident the deep bedded facility would address environmental concerns, improve feed efficiencies and animal comfort and provide additional manure values.

“This is relatively new technology, but I’ve never seen one that doesn’t get really good results,” Russell says, adding that successful producers practice ethical animal care and handling procedures.

Russell shares other benefits to a deep bedded facility, including the possibility of reduced fertilizer expenses because of the higher manure value. The producers also provided anecdotal support for the facility. “The summer of 2012 was very hot and feedlots around the area were losing hundreds of head of cattle. The producers told me they saw one calf panting, but did not lose any animals. That was a good example of animal comfort,” he says.

“There are always concerns when you invest this kind of capital,” Russell says. For instance, they investigated the location to account for future growth. This operation also has a substantial portion of rented acres and any changes would affect the operation’s overall stability. “This is a risk that many farms face, which is why good landlord relationships are very important,” he says.

The building has now been in operation for several years and has been proving the investment was a wise decision. “They told me they wished they had done it years earlier,” Russell says.

Web Exclusive: Expert Responses

Click below to view other case studies from this report: