If you don't know what collectible efficiency is, it's likely that you're not seeing the profits you should be from your service area.

If you've ever wondered why your service department never seems to make money — or worse, if you're not sure if your service department is making money — then it's time to step back and reevaluate your backroom operations.

Greg Schneider, a trainer with Spader Business Management, says there is simply no excuse for not knowing what kind of money is moving through your service area.

He talks about the dealer mentality in the '70s and '80s, where there was a "fishbowl" model of accounting. In the fishbowl model, overhead and expenses were represented by a large empty fishbowl and money from every department was poured in to fill it. Hopefully, at the end of the month the fishbowl was full, but even if it was overflowing there was no way to monitor how much individual departments were pouring in compared with how much of the empty bowl they were responsible for.

With the widespread use of computers and software in the 1980s and '90s, dealerships were able to move away from this model and begin concentrating on the "wheel and spoke" model. In the wheel and spoke model, every department in a dealership is set up as its own personalized profit center. Income and expenses are individually monitored for the sales, service and parts departments, and each one of the three "spokes" is responsible for a share of the overall business expenses and expected to be entirely self-sustaining.

With how much easier it's become to monitor individual performance of each department, Schneider says he's surprised when he runs into dealerships that don't. It's impossible to know whether a department is making money unless there are detailed records kept on income - and expenses.

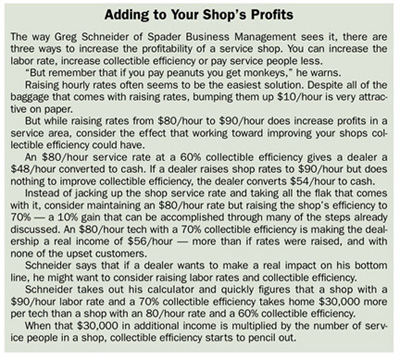

Schneider maintains that in order for the service shop of an ag dealership to break even, the shop has to have an effective labor rate of $55-65/hour. If you just breathed a sigh of relief because your labor rate is $80 or $85/hour, or even $100/hour, you need to keep reading.

The problem, according to Schneider, is that even though a technician is earning a shop rate of $80/hour, he only collects on that rate while he is working on billable hours — that is, he only makes the dealership money when he is working on equipment paid for by the customer.

Because technicians aren't always efficient, and because they don't always fill their days with billable hours, the $80/hour rate may be a long way from what is actually collected.

Dealers and technicians in Spader's Service Management course share different ways they've increased profits in their service department. Spader has helped dealers better understand their businesses for more than 30 years.

For example, say a tech works 8-5, says Schneider. If he's on an hourly wage, he's being paid for 8 hours of work each day. That isn't to say that he's bringing in 8 billable hours, but he gets paid whether he's working on equipment or not.

That's where collectible efficiency comes in.

Defining Collectible Efficiency

Collectible efficiency is the measurement of the difference between hours worked and hours collected. It's unreasonable to expect that a technician will be working on billable hours the entire time he's on the clock, and collectible efficiency measures what percent of the time he is. So, if a tech is punched in for 8 hours, but only records 4 hours that can be billed outside the shop, his collectible efficiency for the day is 50%.

A 50% collectible efficiency isn't a problem for dealership - at least not if the shop's service rate is $130/hour. According to Schneider, the break-even point for most service departments falls at approximately $55-65/hour. That is, after factoring in the overhead of the shop, and making sure the service department is responsible for its share of operating expenses as laid out in the "wheel and spoke" model, a service shop needs to bring in $55-65/hour of real income to break even.

That's why, in the above example, the dealer who thinks he's safe with an $80/hour shop rate needs to step back and reconsider. For a dealer charging $80/hour in his service area, in order to bring in enough money to keep his shop in the black he needs to be running at an 81% collectible efficiency — a tall order for even the most well-oiled technicians.

The problem is that the average tech, if left to his own devices, generally runs between 35-40% efficient. At an $80/hour rate, that leaves your dealership at right around $30/hour of actual income — or about half of what you need to break even.

With these few simple calculations, it doesn't take long to see how important monitoring your shop's collectible efficiency is.

Measure to Manage

The minimum acceptable collectible efficiency in an ag service shop should be 60%, according to Schneider, but even then a dealership needs to have a shop rate of $110/hour to reach the $65/hour break-even point. He says not to worry. With a few tweaks the ag industry is able to consistently run above a 70% efficiency.

Getting There

The first step to increasing techs' numbers is monitoring them. Schneider holds up a pen and says that it is the most important tool a dealer can teach his techs to use.

He jokes that managing collectible efficiency is only as difficult as getting a technician to take notes and monitor his time. Understanding how trying this can be, Schneider offers a solution for dealers with difficult techs. "No notes, no pay," he says. "I'm only going to pay a tech for the time he has documented. If there aren't any notes telling me what he was doing, I'm going to assume that he wasn't working."

This sorts the issue out quickly, Schneider says.

It might be a pain to get technicians in the habit of keeping notes, but the only way to know if the service department is making money is to monitor how they're managing their time. The idea is to record every minute the technician is on the clock, and make sure that all hours are accounted for.

It isn't a matter of trust, according to Schneider, but a matter of accountability. If you don't know what a tech is doing all 8 hours he's punched in, there's no way you can measure his efficiency.

"Have you ever considered how much time your techs spend on coffee breaks?" he asks. He runs through the math and shows how 30 minutes in daily coffee breaks projected over a full work year yields 125 hours of time a mechanic is getting paid and not working. This dwarfs their 80 hours of vacation or the 40 hours of sick leave. At $80/hour, coffee breaks alone cost a dealership $10,000 in possible income each year — per technician.

Schneider isn't saying that coffee breaks should be eliminated, but that they should be rigidly kept to 30 minutes per day and recorded. He takes the math further and shows that a 5 minute spillover per break can cost each tech $3,300 in revenue per year.

Improving Efficiency

It's no surprise that Schneider's advice to increase collectible efficiency is to limit time wasted in the shop. This includes spillover on coffee breaks, but Schneider cites the tool truck as a efficiency-eater as well.

"If your dealership is like mine was, you've got three different tool trucks rolling into your yard." It wouldn't be so serious, he says, except somehow techs find an excuse to visit each truck every time it's in. Remembering how much a 5-minute spillover on a coffee break hurts income, it's easy to understand how 20 minutes with the tool man here and there can add up.

In a perfect world, Schneider would tell tech's they get to choose one tool truck to buy from. Understanding the fallout that might cause, though, he instead advises meeting with all of the different tool suppliers and limiting the time of day they can show up.

"If they want to buy from every tool truck that comes into the yard, or shoot the breeze with every tool man, I'll let them. But I'm also telling that tool truck that if he wants to sell at my store he'd better show up before we open, after we close or during lunch."

Time wasted isn't the only issue draining the efficiency of service departments.

"Just because a tech is productive, doesn't mean he's efficient," Schneider warns. He notes that a technician working all day on a company truck or a broken overhead door is perfectly productive. All of his time is accounted for and at the end of the day he has something to show for his work. The problem is that the dealership doesn't have anything to show for it but a day where a tech achieved 0% efficiency.

He recommends limiting the time techs spend on non-billable jobs and adds that these are just as bad as long coffee breaks. A technician plowing snow when work is piling up doesn't make the dealership any more money than if he were talking to the tool man.

"If there isn't a wrench in a tech's hand, he is costing you money," says Schneider.

To illustrate the point he draws up a scenario where a tech making $30/hour is asked to change the oil on the company truck. He might be able to do it in 30 minutes and the dealer figures the oil change costs him $15. The dealer saves $10 over what it would have cost him at Jiffy Lube, but chalks that up to the benefits of owning an ag dealership.

"A 50% collectible efficiency isn't a problem for dealership — at least not if the shop's service rate is $130/hour..."

But say the tech wrote up a service order for that owner. All of a sudden an $80/hour labor rate plus parts (with markup), and what the owner thought was $15 of his tech's time turns into an $85 bill for an oil change.

That's what the oil change is actually costing the bottom line of the dealership. The tech's time would have been better if collecting billable hours rather than spent on a company truck. When dealers start looking at their shops as a customer would, it suddenly makes a lot of sense to take the trucks to Jiffy Lube or contract a service to plow your lot.

Schneider suggests limiting the time that techs spend on non-collectibles and increasing efficiency by hiring a yard man to take care of the odd jobs around the dealership. The yard man can plow snow, move tractors in and out of the service area or clean machinery before it is ready to go back to the customer. Schneider believes that a year-round yard man can bump up collectible efficiency by 5-10% just by keeping the techs off non-collectibles.