Update 5-14-23: International Harvester's Farmall Plant Marks 38th Anniversary of Final Tractor Production

Editor’s Note: An autographed copy of The Break-Up by Paul Wallem was lent to me by machinery dealer consultant George Russell during a visit to our offices in July 2019. After a quick read of the 192-page book and the novel examination of the tumbling of the farm equipment giant from the equipment dealers’ perspective, we requested permission to share an excerpt of the book’s content with Farm Equipment subscribers. What follows is a small portion of the book’s content, in the author’s own words. In total, Wallem (an IH executive and later a dealer himself) interviewed 28 North American dealers, with first-person accounts of the events that transpired. Released in the spring of 2019, The Breakup is now in its second printing and is available from Heritage Iron magazine. -- Mike Lessiter, editor/publisher

The Breakup examines the reasons International Harvester failed in 1984 (and its merger with J.I. Case), with IH dealers and customers weighing in with their opinions.

Being a dealer is more than a job. It’s a way of life, and owners often invest everything they have. Dealers are the lifeblood of a manufacturer. Harvester built over 5 million tractors prior to 1984. Every one of them was sold by a dealer somewhere, yet dealers go unmentioned in the various books about IH history.Interviews were conducted throughout the U.S., Canada and Sweden, and include discussions with former IH and Case IH company personnel involved in the transition.

Dealers and their farmer customers voiced their recollections about the merger, ranging from shock and despair to optimism for the future. Strong sentiments were expressed during some of these interviews.

“I felt like I lost my family,” said Larry Smith of O’Neil’s Farm Equipment in Binbrook, Ontario, when he learned that Tenneco had purchased International Harvester’s farm equipment division.

Shocking News of November 26, 1984

IH dealer Fran Read heard the shocking news on the radio that Tenneco had purchased the International Harvester farm equipment division. His comment to son Bob? “The sleeping giant is dead.”

The breakup of International Harvester Company did not happen suddenly, however. Many feel the trouble started long before 1984, as the company over-extended its ability to manage and provide capital for participation in multiple industries.

Significant timelines:

• 1831 -- Cyrus Hall McCormick invented the mechanical reaper. This very basic machine mechanized grain harvesting for the first time and became the origin of International Harvester Company.

• 1902 -- McCormick, Deering Harvester Company, Plano Manufacturing Company, Champion Line and Milwaukee Harvester Company joined forces to create International Harvester Company. The newly-formed conglomerate offered a larger variety of farm machines. During the early 1900s, husker-shredders, beet harvesters and many more new innovations were brought to market. Early tractors, however, were drawing the most attention.

• 1923 -- The First Farmall tractors were built, and in 1924, 205 were sold at a price of $825. By 1932, the number produced had totaled 134,954, as the Farmall series forever changed the way farmers raised row crops. The Farmall continued to be a huge success. Between 1939 and 1953, the company built 391,730 of just one model, the Farmall H. To this day, it is the largest number of any model farm tractor ever built.

The Farmall Works entrance in 1984 at the time the announcement came that the Rock Island Plant was to be plant was to be closed. (Photo by Harry Boll/Quad-City Times)

Fast forward ... A Corporate Tragedy by Barbara Marsh was published in 1985, the same year the Case IH merger was finalized. It is recognized as an in-depth account of the breakup of International Harvester Co.

Significant parts of the book were derived from a two-part series published by Crain’s Chicago Business 3 years earlier. That article was entitled “International Harvester’s Story: How a Great Company Lost Its Way.”

The following paragraphs are from A Corporate Tragedy:

“Following World War II, the company’s arrogant pride in its heritage blinded executives to the challenges of the modern world. An ill-conceived pursuit of a broad array of capital-intensive businesses gradually sapped the company’s financial strength. Wallowing in inertia, Harvester couldn’t muster the strength to invest sufficiently in its diverse bundle of capital-hungry businesses and lost ground to Midwest competitors of vision, determination, and resources.

Harvester relinquished its ancient leadership in farm equipment to its archrival, Deere & Co. of Moline, Illinois. In construction equipment, Harvester remained a hopelessly distant number two behind the industry’s colossus, Caterpillar Tractor Company of Peoria, Illinois.

In the truck business, Harvester fell behind the Detroit automotive giants, who enjoyed economies of scale by using common components across their car and truck lines. At the same time, Harvester’s high labor costs — a vestige of the company’s long, stormy history of relations with organized labor— exacerbated its competitive disadvantages.

In the early 1970s, Brooks McCormick and his chief lieutenants had set their sights on improved profitability, and by 1976 Harvester had started perking up. Between 1971 and 1976, its earnings grew nearly threefold to $174.1 million. Return on sales more than doubled to 3.2% from 1.5%. Return on assets more than doubled to 4.9% from 2%, and return on equity leaped more than threefold to 12.1% from 3.9%. But Wall Street analysts were not impressed as Harvester still continued to lag behind its competitors on all accounts. Even prospects for a cyclical recovery in Harvester’s markets following the mid-1970s recession offered little consolation: The company’s profit margins were ultra-thin and its debt burden heavy.”

One significant attempt to enlist dealers’ opinions was initiated in 1973 by Harvester farm equipment executive Stanley Lancaster. He created the first Dealer Council, to bring dealers together with Harvester management on a regular basis, and exchange views. These group sessions continue today, with varied success.

A long strike lasting from November 1979 to April 1980 further weakened the company. Truck and farm equipment production was continued during the strike regardless of the downturn in both markets. Management erroneously assumed that dealers would be ordering heavily after the strike ended, to replenish inventory.

However, high interest rates and the slowdown in the market had drastically reduced demand in most dealer territories, and they had no need to re-order. Another huge factor entered the picture in January of 1980. President Jimmy Carter imposed a grain embargo on the Soviet Union.

The impact on grain farmers was devastating. The market for farm equipment was drastically diminished. Suddenly the company had yards full of unsold inventory, with large amounts of tied-up capital.

“If only McCardell and Hayford had been listening to Harvester’s dealers during this strike, they would have known that dealers would not require restocking after the strike.”From page 227 of A Corporate Tragedy:

The tied-up capital in unsold inventory further sapped cash reserves and came at a time when the company was already badly needing operating funds and looking for more banks to borrow from. (One of the reasons for writing this book is to again emphasize that dealers were not being consulted, at this or other times. Until a dealer sold a machine, the company had no income. Yet through the years, the dealer’s opinions were not requested. I was a dealer during these years, and personally felt that my opinion was not wanted by top management. Most of the dealers interviewed for this book felt the same way.)

Finally, at long last, Harvester’s Board of Directors voted to eliminate the company’s annual $1.20-a-share common stock dividend. From 1981 until 1984, over 200 banks worldwide were utilized to keep the doors open.

From page 278, A Corporate Tragedy:

“By 1983, a drastically shrunken Harvester had sales of $3.6 billion, placing it 104th on the Fortune 500. It ran up losses of $485 million that year, making a total of nearly $3 billion in losses for 1980-83. It employed 32,000 workers worldwide, including 19,000 in the U.S. It had trimmed its overextended industrial empire back to three businesses: farm equipment, trucks and engines, and it held just 27 plants around the world.

Harvester’s massive contraction was the inevitable step for a company that had never come to grips with its own limitations. It had long been a marginally profitable, overly diversified, and thinly capitalized corporate monolith. It had been saddled for decades with a complex of intertwined problems that none of Harvester’s post-World War II executives could resolve.

The company’s arrogant pursuit of too many capital-intensive markets had slowly sapped its strength while its well-managed corporate rivals had predominated by strategically channeling their resources.”

In the fall of 1983, Irv Aal was New Holland’s Vice President for North America when he was hired by International Harvester to keep the farm equipment division alive. He was instrumental in bringing Tenneco management together with IH leadership.

By the fall of 1984, all options had run out, and the banks throughout the world had had enough. Harvester management looked for a buyer, and Tenneco, owner of J.I. Case, was the one that stepped forward. On November 23, 1984, the deal was finalized. Almost three months later, during February 1985, the transaction was completed. The IH farm equipment division became part of Case IH. The portion of International Harvester that was the truck division became Navistar.

Harvester’s gloomy announcement on November 26, 1984 of plans to sell of its loss-ridden farm equipment division after more than 150 years in the industry. (Source: Roger Schillerstrom, Crain’s Chicago Business.)

Thirty-three years later, on June 12, 2017, Irv Aal said to me, “The IH dealers were the greatest off-balance sheet asset that Tenneco purchased. Their loyalty to the brand was amazing. They bled red paint.”

When I worked directly for IH (1956-1968), one of my first assignments was territory zone manager. I called on 21 dealers in central Wisconsin. They were small businesses, run by self-made individuals with a lot of common sense. They often complained about too many in-field failures (such as the 816 mower conditioner). Another was the final drive failure in the Farmall 560. Dealers often said back then that more testing should have been done on the farms. Some customers were lost permanently after they had suffered downtime from these mistakes.

Another contentious disconnect between International Harvester and its dealers was in facilities. During the 1940s and ’50s, dealers were pressured to build a new facility called the prototype building. The company wanted all dealerships to look alike.

Yet the company’s facilities were antiquated in some significant areas. Farmall Works, for instance, was a 1926 building, and by the 1970s and ’80s, had become inefficient compared to the modern tractor plant of its main competitor, Deere. (My dealership would take busloads of customers to Farmall Works during those years to see tractors being built. Often, I heard comments about how old the building looked.)

During 1966-1968, I was Harvester’s farm equipment export manager. What was obvious from trips to the English and French manufacturing plants was the age of these facilities. They were old and outdated. One contrast was the IH engine plant in Düsseldorf, Germany. It was modern and efficient.

The older dealers interviewed for this book expressed their deep disappointment that the breakup happened. Many of these business owners did continue as Case IH dealers, and continue to be dedicated to their employees, customers and communities. New dealers that got into the business following 1984 are enthusiastic about the industry and are showing as much pride in the Case IH brand as did the older generation of IH dealers.

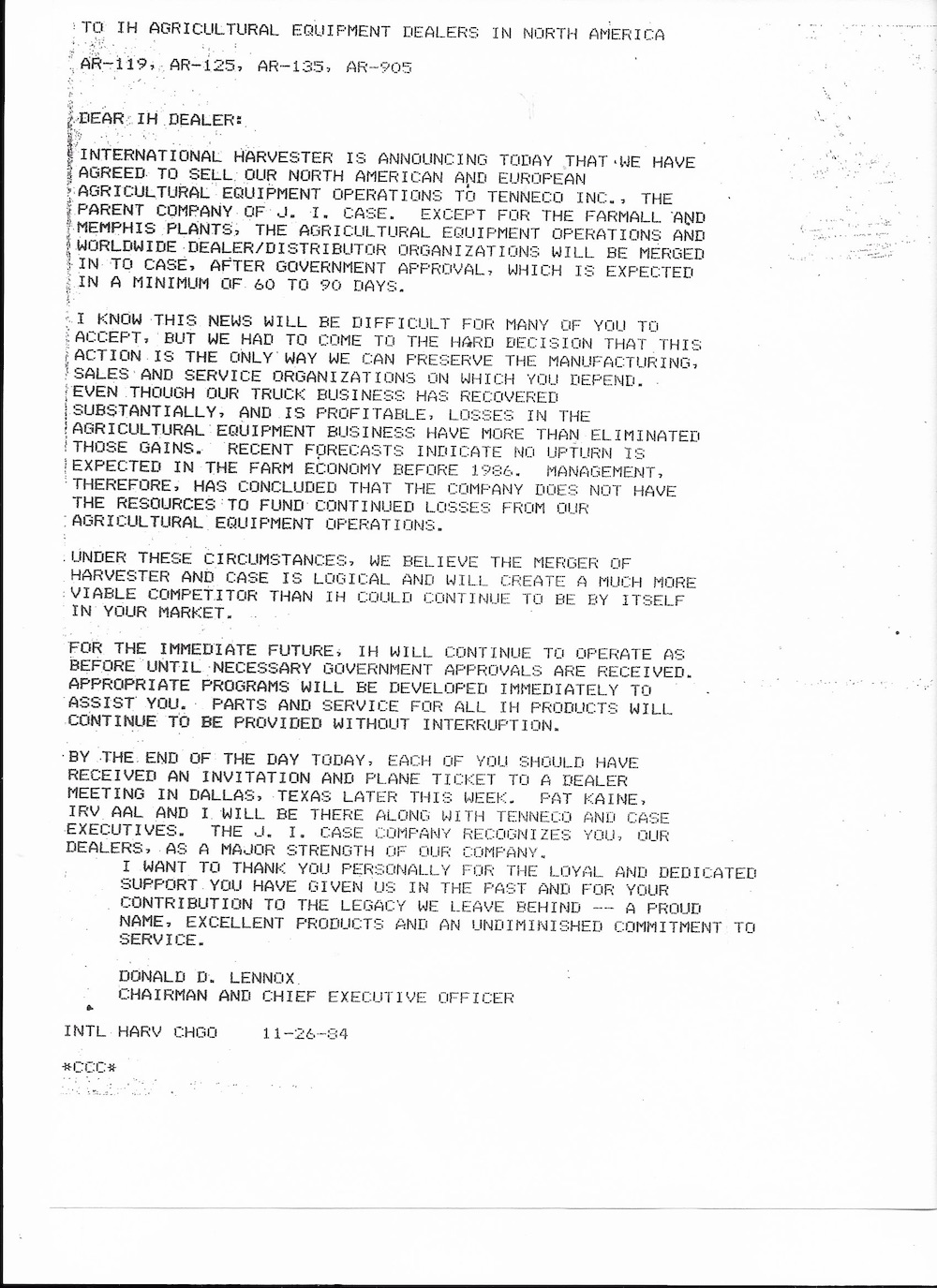

Official correspondence from Don Lennox, International Harvester (IH) Chairman/CEO, on November 26, 1984, announcing the decision to sell to IH to Tenneco Inc., the parent company of J.I. Case.

IH Profit Margins ... Going South

Strong profit margins are important in order to invest in research and development, and to keep products competitive. Low profit margins over a long period had a devastating impact on International Harvester.

The final loss of IH independence in 1984 came after a long period of profit margins below those of its competitors. Traditionally, IH farm equipment had been the largest product line, even though the truck division had grown rapidly. The construction equipment division had been expanded through acquisitions. Profit levels, though, were below the competition in all three markets, dating back to the Great Depression.

| Company | Great Depression Profit Margins |

| International Harvester: | 9.7% |

| Deere & Company: | 18.5% |

Source: Corporate Tragedy by Barbara Marsh

During the five-year period 1956-1960, Harvester continued to trail the competition in all three markets: farm equipment, trucks and construction.

| Company | Profit Margins 1956-1960 |

| International Harvester: | 3.8% |

| Deere & Company: | 7.2% |

| General Motors: | 7.5% |

| Caterpillar: | 6.4% |

In 1958, Deere unseated IH as the world leader in farm equipment sales volume and, to this day, has never relinquished first place. Deere and other IH competitors had used their superior profit levels to invest in more modern manufacturing facilities, and through the years, IH also suffered from poorer union relationships.

Ultimately, the low profit returns and labor problems forced Harvester to accumulate ever larger debt and invest less in research and development. Management errors in dealing with these challenges finally forced an ultimatum from over 200 bank lenders and forced the breakup.

Leadership (or Lack of) During Final Years: Archie McCardell

Following is the Archie McCardell obituary, published in Business Day, July 16, 2008:

During August 1977, Archie McCardell became president and COO of International Harvester Company. Previously president of Xerox, he was then elevated to CEO and Chairman in June 1979.

Upon his arrival Mr. McCardell began an aggressive program to cut costs and engineered a profit increase in his first year, to $370 million from $203.7 million. But Harvester’s margins were only a little more than half those of its competitors Caterpillar and Deere & Company. This had resulted in part from past concessions to labor and a tradition of paying out most earnings as dividends rather than investing them.

When the United Auto Workers contract expired November 1, 1979, Mr. McCardell saw an opportunity to improve efficiency by persuading the union to give up rights it had won in past negotiations, particularly on overtime.

The union went on strike for nearly six months and eventually retained most of the work rights Mr. McCardell had sought to take away. Harvester had lost $479.4 million during the strike and 397.3 million in its 1980 fiscal year.

Union members complained that Mr. McCardell and his lieutenants only heightened tensions by acting arrogant and aloof during the strike, in one instance, they said, sending armed guards to watch dismissed workers clean out their lockers, the New York Times reported in 1982.

Another flash point was McCardell’s compensation package, which included a $1.5 million signing bonus and a $450,000 annual salary — astronomical figures for executive compensation then, but modest by today’s standards. Workers as well as shareholders were also furious when the company forgave a $1.8 million loan to Mr. McCardell.

The labor problems only added to the company’s woes. Climbing interest rates, weak markets and high-cost plants had helped push Harvester’s debt to $4.5 billion. Only through an agreement with 200 lenders in 1981 did Harvester escape bankruptcy.

Mr. McCardell resigned in May 1982, although Time magazine and other publications suggested that his departure was really a firing. “The real wonder was that McCardell had not been ousted much earlier,” Time said.

International Harvester did not recover, and in 1985 it sold its farm equipment division, which started with Cyrus McCormick’s reaper factory. Its crimson tractors and combines had long been a familiar feature of the American heartland. The remainder of the company, its truck and engine division, became the Navistar International Corporation in 1986.

Six months after Mr. McCardell left Harvester, he spoke to a group at Harvard Business School. He said he had two regrets: the controversial nature of his compensation deal, and not getting to know union people better before the strike.

Asked to grade himself, Mr. McCardell nonetheless replied, “I think I rate myself superb.”

“Their decision-making was flawed,” was a line from the 2017 film, The Post. So it was at IH.

Memories from Irv Aal

“A bit of history: I joined IH’s Ag Equipment Group as a senior VP on October 1, 1983, after several months of deliberating whether to make the career move after spending 22-plus years at Sperry-New Holland.

“I convinced myself the opportunity versus the risk was worth it, believing the worst of IH’s financial problems were behind it after IH negotiated a comprehensive refinancing package with over 200 banks. IH had a long history in the ag equipment market and was recognized worldwide as an icon of the industry.

“As 1984 started, the sales of tractors and combines, after 5 years of torpid sales, deteriorated another 15% from the prior year instead of the industry forecast of a flat or modest strengthening of the market.

“The ag equipment group was losing money, as was the entire IH corporation. Cash flow became paramount and as the season progressed, it became apparent more drastic decisions needed to be made. I received approval to look at any alternatives we could conceive to halt the hemorrhaging of cash.

From l to r, IH’s Irv Aal, broadcaster Orion Samuelson and author Paul Wallem, at Wallem International dealership in Belvidere, Ill., September 1984

“IH had recently introduced the 50 series tractors and due to weak sales, had significant excess production capacity at the Farmall plant in Rock Island. So, we discussed building tractors for other industry players. Since Case’s tractor lineup was dated, we speculated on whether they would even consider such a move. Keep in mind that everybody in the industry was hurting after several years of declining sales.

“I placed a call to Jerry Green, president of Case. He invited me to visit Racine and discuss business. I didn’t indicate precisely what I was going to propose during our phone call. I visited Green at his office toward the end of August 1984. After exchanging pleasantries and the state of the overall industry, I asked if he thought his organization would be willing to discuss the concept of IH’s building tractors in Case colors, and with some modifications they would want.

“Green immediately called Jim Ketelsen, Chairman and CEO of Tenneco corporation, the parent corporation of Case. Ketelsen, when hearing the proposal, said he would like to elevate the discussion to a higher level of management. (Note: It seems that Ketelsen and Don Lennox, then Chairman and CEO of IH, had a brief meeting in Chicago about a year earlier that didn’t produce any positive results, but Ketelsen remained interested in having more conversation and felt the door had been opened with the meeting Green and I had.)

“I agreed to pursue this with the top management at IH. This resulted in a meeting being arranged to occur at the Farm and Industrial Equipment Institute’s annual meeting scheduled at The Homestead in Hot Springs, Virginia.

“A few months earlier, I had accepted an invitation to be the luncheon speaker at the Minnesota-South Dakota Equipment Dealers Assn.’s annual convention in Minneapolis in November. Ironically, the day of the press release announcing the acquisition was the day of my speech.“By the end of the annual meeting, an overarching framework had been reached by the companies’ leaders that culminated in Tenneco Corporation purchasing essentially all the assets of the Ag Equipment Group of IH Corporation The plan was to merge the J. I. Case ag equipment division with IH’s ag equipment group. This resulted in a new brand name and logo: Case IH.

“Needless to say, that caused some anxiety because of the timing of the press release. It had to precede my speech to avoid any problems with the governmental agencies. News of this magnitude would cause ripples throughout the industry.

“Fortunately, I was given clearance to mention the announcement in my speech. That prompted more hand-wringing on my part, because I couldn’t imagine giving the same speech I had prepared. I doubted any person in the audience would hear or retain much of what I had prepared after the news was announced.

“I decided to ‘wing it,’ and after approaching the podium, I pulled out my prepared comments and told the audience I had some news to share before giving the speech, and I doubted they would be very interested in what I had to say after hearing the news.

“I then proceeded to provide a broad overview of the deal. Deafening silence followed. It was difficult, if not impossible, for the dealers who had their lives and livelihoods tied up in their businesses to comprehend the implications of the announcement. After a brief time for the audience to absorb what I had just said, I proceeded to try and put a positive spin on the deal. The rest of the speech was brief, to say the least!

“The rest of the story has played out over the years, with both winners and losers. It was the first of many consolidations of the industry players over the ensuing years, and when one thinks back to 1984 and compares it to today’s industry, it’s barely recognizable.

“Time has a way of leveling out the peaks and valleys, but to the people in the room that day in November of 1984, it will always be indelibly etched in their minds.

“When the announcement was made on November 26, it was a momentous time in the history of a proud corporate giant. Rumors had been circulating in the press that IH was looking at what further steps it needed to take to survive. But, when the announcement was made, the reaction within the company was utter disbelief. People were stunned to think that the company that traced its roots back to 1831 was now going to be part of Case. It was a challenging time for me, also, since I assumed (correctly) that I would not be part of the new organization. However, as president of the ag group that was sold, my main concern was for the employees and their families, in addition to the impact on the IH dealer organization.

“Since the sale had to be approved by the Justice Department in Washington, D.C., and not knowing how long that would take, it was incumbent on the management team to maintain a ‘steady as she goes’ attitude, and keep the lines of communication open to mitigate the myriad rumors that were floating around. We planned and executed a comprehensive communications plan for employees, dealers, farmers, suppliers and other constituents.

“We found out it is difficult to make lemonade out of lemons, but we strived to do our best, confident that, while this was a seismic move in the industry, IH had a long history in the marketplace and the products would still be in demand. The challenge was to make it from point A to point B and try to minimize and mitigate the fallout among the employees and dealers.

“The Justice Department approval was announced on January 31, 1985. IH’s ag equipment group was integrated into the Case Corporation and a new brand company was introduced. Case IH was, and continues to be, a strong number two in the industry.”

Why IH Failed: Jim Hitchner

Jim Hitchner spent his entire career with International Harvester. He joined IH right out of college, was rapidly promoted, and spent his career managing the field offices that maintained dealers and obtained new ones.

It was a surprise to hear he had taken early retirement in 1982 at age 58, being disillusioned with new IH leadership. In the summer of 1983, he agreed to return to assist in stabilizing the dealer organization. As the company situation disintegrated, he then returned to retirement.He was highly regarded by the dealer organization. I worked with Jim during my years with International Harvester, and shortly after I resigned to buy a dealership, he became the regional manager for the territory I was located in. I respected and admired his business sense, and his attention to dealer concerns.

This background information is provided so that you can understand why his opinions are of value. Below are his comments in January 2018.

“I would put the reason why IH failed in just two words: Horrible management. Overall, from Brooks McCormick on down, there was much lacking. By choosing McCardell, we went from the frying pan into the fire.

“We had prolonged strikes, but here again, that was a failure of management decisions. Management often did not take the positions needed. I can remember when live PTO (power take-off) was the new needed feature. Management said the customer would buy our tractors without it. This cost us in customer loyalty.

“It is also true that we got into too many industries, which strained our cash flow. There was no reason for a great company to slide so far, so fast. The main culprit was horrible direction from our leaders.”

My Memories as Dealer in the 1980s (Wallem International, Belvidere, Ill., and Central Sands International, Plainfield, Wis.)

Between 1970 and 1986, IH arranged visits to Wallem International for people from 25 countries. Many of the groups were in the U.S. to visit various agricultural suppliers, farmers and universities. At Wallem International, they would see a typical ag equipment dealership in operation. Following a 1977 visit by three Soviet Union officials, an article appeared in the Rockford Morning Star. The Cold War was still in full force, and tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union were high. Soon after, I received a call from the Rockford FBI office, wanting to talk to me about our visitors. The agents came to the store and wanted to know, in detail, what the Soviets had been talking about, what questions they had, etc. I did my best to reassure them that everything my visitors and I talked about involved agriculture.

At an IH dealer meeting in Decatur, Illinois, in the early 1980s, one of my fellow dealers commented over lunch that the state of the business was causing many sleepless nights, that he often woke up about 3 a.m., worried whether his dealership could survive. Another dealer quickly agreed, saying he often did the same. A third dealer, at the end of the table, said IH might as well have future dealer meetings at 3 a.m. because it sounded like we were all awake at that time, anyway.

That was one of the rare light moments during a troubling time for our customers and for us.

Only a few years earlier, both of our IH dealerships were doing well. In 1979, crop prices were good, and the Axial-Flow combine was a big hit. In October of that year, our Belvidere, Illinois, store sold and delivered 12 new combines. For the full year, over two dozen were delivered.

The proximity of Wallem’s Belvidere, Ill., dealership to the Chicago IH headquarters — an hour’s drive — laid the groundwork for numerous foreign visitors.

Partner Bill Kleckner left a successful career with IH Export Company to manage our Central Sands International dealership in Plainfield, Wis. It was also having a strong year, not only with IH equipment, but with sales of Zimmatic center pivot irrigation systems.

Storm clouds were gathering, however, which would have a huge impact on us in the years to follow. The prime rate had risen from 11.75% at the end of 1978 to 15.75% at the beginning of 1980. By itself, the interest rate didn’t cripple our industry, but the storm had yet to begin.

Another big cloud on the horizon was the IH union strike, starting in November 1979. It lasted almost 6 months.

Then, on January 4, 1980, the roof fell in. Not only was the strike shutting off our parts supply, (the manufacturing plants were shut down, but we weren’t selling any machinery anyway) but President Jimmy Carter announced a Russian grain embargo. Prior to that day, projected grain export estimates to Russia for 1980 totaled 124.6 million metric tons. After the embargo was announced, the estimates fell to 107.1 million metric tons. As a result, grain futures fell dramatically. Our customers stopped shopping for equipment, new or used. Most farm machines are big-ticket items and must be financed. The increased cost of interest along with the grain embargo and lower grain prices shut down our sales.

Then things got worse. By the end of 1980, the prime rate moved up to 21.5%, to this day the highest in U.S. history. As a result, all machinery sales dried up, a drought that lasted almost four years. We had well over $1 million in machine inventory, subject to interest. None of it was selling. Even worse, was the lack of used equipment sales, which typically provided monthly cash flow. It all just sat on the lot, drawing a higher rate of interest than the new equipment.

Now add this to the story. I was a board director at our local bank. The rules of the Comptroller of the Currency stated that a director borrowing from the bank he was involved with must pay 1% over prime on any loans he took from that bank. So, I was paying 22.5% interest on equipment that I couldn’t sell at any price. Those were interesting times.

By November 26, 1984, when the Case IH merger was announced, the prime rate had dropped to 11.5%. It was too late. Many dealerships (including ours) as well as farm customers had lost much of their net worth.

The nightmare was continuing for American farmers. Lower grain prices reduced their income. Higher interest rates increased their borrowing cost. Because of all this, their land had decreased in value, and in many cases, that was the equity their loans were based on. Many couldn’t get their credit lines extended and were forced off the farm.

Each Monday, my office manager at the Belvidere dealership went to the courthouse to pick up the prior week’s bankruptcy filings. During the early 1980s, we would often see our customer’s names on these reports. Many had open accounts at our store, some with past-due balances in the mid-four figures as a result of engine overhauls in our shop. The minute I saw their names on the list, I knew we would never see the account paid. That was a sick feeling every time.

I vividly recall the day one of our dairy farm customers came to my office, shut the door, sat down and told me he had declared bankruptcy. He lived near the dealership and had become a friend as well as a customer. He cried. I felt bad for us.

I felt worse for him.

Another customer with whom we had worked for years, came in at the height of the harvest season and bought a combine. He had always had good credit, and I was certain his credit application would be approved. But it wasn’t. That call, telling him we needed the combine back, was a hard one to make.

I recall visiting a dealer in an adjoining state to buy a used truck. He and I discussed the common problems we were having in agriculture. My recollection was that he was dealing with the challenges, just like the rest of us. Yet two days after our visit, he entered his parts department after closing hours and shot himself. Suicide became a frequent solution for many people in agriculture during those dark years.

Finally, in 1985 after the Case IH merger, there was a bit of light. With the prime rate down to 11.5%, farmers started buying again, and the dealerships that were still in business began to recover. I recall hearing that 11,500 farm equipment dealers of all colors existed in 1979, but by 1985, only 5800 remained. If we assume that the average dealership throughout the U.S. employed about 18, that meant almost 103,000 lost their jobs.

The years have passed, and the world of agriculture has moved on. The Case IH merger actually carried forth the IH product engineering, quality reputation, and customer loyalty.

International Harvester’s European Organization

Outside the U.S., International Harvester Company operated numerous subsidiaries. A large number were located in Europe. The largest were also operating manufacturing plants.

A 1966 summary of the European operations are listed below, alphabetically.

- Belgium -- International Harvester Company of Belgium S.A.

- Denmark -- A/S International Harvester Company

- France -- International Harvester France (Factories: Croix Works, Montataire Works, St. Dizier Works)

- Germany -- International Harvester Co., mbH (Factories: Nieuss Works, Heidelberg Works)

- Great Britain -- International Harvester Company of Great Britain, Ltd. (Factories: Bradford Works, Carr Hill Works, Doncaster Works, Liverpool Works)

- Spain -- International Harvester de Espana S.A. (Factory: Seville Works)

- Sweden -- AB International Harvester Company (Factory: Norrköping)

- Switzerland -- International Harvester Company AG

During the years before 1984, International Harvester Export Company maintained its European Planning Office in Brussels, Belgium. Similar export offices were in Lima, Peru, Beirut, Lebanon, and Singapore.

The years have passed, and the world of agriculture has moved on. The Case IH merger actually carried forth the IH product engineering, quality reputation, and customer loyalty.

Dealers View on Why IH Failed

Many of the 28 dealers interviewed for this book were in dealerships well before the 1984 Case IH merger. Some (like myself) have fond memories of the ’70s. Farm prices were favorable, and business was good. The arrival of the Axial-Flow combine, in particular, gave Harvester dealerships a big boost.

Then the storm hit. The dealers interviewed for this book were asked why they thought IH failed. Here are some of their thoughts:

- Cash crunch hangover from 1979-80 US strike

- Worldwide slowdown in the 1980s for IH products

- Too much short-term debt

- High interest rates

- Did not focus on core products

- Bad union contracts

- Shareholder dividends paid for too many years

- Not enough R&D during late ’70s and ’80s

There were additional insightful comments, but several dealers summed it up this way: “Weak and ineffective management.”

This quote is from the Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1983 by S.F. Lancaster, 1983-85, VP Agricultural Marketing, after the departure of CEO Archie McCardell: “McCardell’s biggest mistake by far was the infusion of people not familiar with what makes us tick.” In a later interview, Lancaster commented, “Revolving doors of CEOs took a toll.”

Now, all these years later, we can reflect on what might have been. Had the Case IH merger not occurred, the products and dealers represented by the Case IH logo probably would not exist. All the great history and technology behind these two trademarks would be lost. Thousands of employees of the companies and dealers would have been jobless. Many farmers would have struggled to find parts and service for their equipment. In all probability, the value of their machinery would have dropped.

Since the IH merger, however, many customers have stayed loyal to red equipment. Dealers and farmers who were interviewed for this book felt that it all turned out well. The merger of IH and J.I. Case assured that both survived to share a 175th anniversary in 2017.

Case IH has become a major innovator of agricultural equipment technology. Some dealers have already or are about to celebrate their 100th anniversary. A few have fifth generation family members involved. Some have old customers who are also into their fourth or fifth generation. Trust runs deep in these relationships.

Paul Wallem Bio & Observations on the Dealer

Many of the dealers and customers interviewed for this book say they recall their first red tractors between ages five and eight. For me, it was seven, and I remember that because my older brother was just leaving for the U.S. Navy, and our neighbor drove over with his new Farmall M.

Our high school at Streator, Illinois, allowed seniors to leave school at noon if they had an apprentice job. I worked that year as an apprentice mechanic at our local IH dealer, Melvin Sales Company. I learned what cuss words worked best as we assembled the tin work on 2M corn pickers. (I’m lucky I still have all ten fingers.)

During my freshman year at the Univ. of Illinois, Melvin Sales became an IH company store, and I worked there as a salesman part-time when home from college. That opened the door for me to work directly for the IH Broadview, Illinois, District Office one summer as an intern. About this time, I started realizing how important IH had become to me. Could I spend my life with this company?

Broadview District Manager Bill Moulder said if I worked hard enough, I could. So, I spent the next 13 years with IH, in the following jobs:

- Broadview District Assistant Zone Manager

- Madison District Zone Manager

- Madison District Sales Promotion Supervisor, then SPK

- Peoria District Sales Manager

- National Product Supervisor, 424, Cub Cadet, Ag TD6 crawler

- 12-month management training program, with time at all divisions

- Worldwide Farm Equipment Export Manager

Looking back, I think zone manager was the best of all jobs. Calling on dealers every day was a better education than my Ag degree from the University of Illinois. The dealers pulled no punches, worked six days a week, constantly questioned why IH wasn’t field testing more before shipping equipment that needed fixing later. In the meantime, they were fiercely loyal and great competitors.

I had that zone manager job in the late 1950s. The 816 mower conditioner couldn’t make it across the field without breaking down. The 560 bearings were calling it quits. Unhappy customers wanted their dealer to let them know when the company rep was coming. (That was me.) These were challenging days.

Throughout my later jobs, the thought stayed with me that the dealer was totally in control of his destiny. No one could fire him. He had no boss looking over his shoulder, unless it was a banker. He either failed or succeeded. He decided who would work for him.

Following that earlier zone manager assignment and my district jobs, my first national responsibility was the sale of 424 tractors, Cub Cadets, and TD6 crawler tractors for ag use.

The next assignment made me realize how big Harvester had become. I was placed in a 12-month general management training program and started spending time at facilities of each division: farm equipment, truck, and construction equipment. Part way through that program, I was offered the position of worldwide farm equipment export manager, for the farm equipment division. This was an exciting and challenging assignment and took me to 52 countries over a two-year period.The TD6 was built by our construction equipment division, and we were a distant second to Cat in that market. (I never stopped wondering why we were even in that market. Finally, by 1983, IH management realized it was a drain on resources and sold that division.)

We maintained offices in Beirut, Singapore, Brussels and Lima. I spent time with the reps at each office every year, contacting our distributors and establishing new ones.

My family lived in Mount Prospect, a suburb near Harvester’s Chicago headquarters. The company occupied 12 floors in the new Equitable Building, located along the Chicago River in downtown Chicago on the site of the McCormick Reaper Plant built in 1849.

These were not easy years for my family, as my wife was alone most of the time, raising our six- and 10-year-old children.

During these years, I was puzzled why we had an Overseas Division when other large companies were eliminating that layer of overhead. Their domestic divisions had taken on the responsibility of worldwide marketing. Also, I started remembering all the freedom that the U.S. dealers had. They were controlling their own destiny, and home every night.

Nearing the end of a five-week stay in Europe, I called home to say I had decided to resign and find a dealership to buy in the States. This was quite a shock to my wife, Joan, as we had been told to move to London in two months, and work with International Harvester Great Britain.

So, I resigned from the company and for 17 years owned and operated our two dealerships. A huge benefit of this was that my children grew up around the dealership, and I saw them every night. My oldest son, Jeff, worked at the store during high school, and IH hired him as a summer intern during college. After graduation, he joined the Quad-Cities region. While he was working as a zone manager in Iowa, we agreed he should help me run the dealership, which he did until we sold it. My daughter, Linda, worked in the parts department during a summer in college, and my youngest, Stephen, spent time in the shop. And because I worked a six-day week for 17 years, my wife, Joan, took care of the house, the kids, and me.

As of the publication date of this book in 2019, Joan and I have been married 62 years.

Part 1: "Shocking News of November 26, 1984"

Part 2: "IH Profit Margins ... Going South"

Part 3: "Leadership (or Lack of) During Final Years: Archie McCardell"

Part 4: "Memories from Irv Aal"

Part 5: "Why IH Failed: Jim Hitchner"

Part 6: "My Memories as Dealer in the 1980s (Wallem International, Belvidere, Ill., and Central Sands International, Plainfield, Wis.)"

Part 7: "International Harvester’s European Organization"

Part 8: "Dealers View on Why IH Failed"

Part 9: "Paul Wallem Bio & Observations on the Dealer"

View the Image Gallery: "The Breakup of International Harvester and “What Really Happened”

Watch the Slideshow: [Video] The Breakup of International Harvester and “What Really Happened”

Explore more on the International Harvester breakup: