The future of farm equipment distribution in North America is being reshaped in ways and by means that many dealers could not have imagined a decade ago. And there's one thing that dealers can count on: there will far fewer of them when this decade ends than when it began.

Since the start of the new millennium, the majors have used a number of tools to "streamline" their distribution channels and assert more control over their dealer networks. From demanding "brand purity" to assigning ambiguous and, in some cases, patently unfair market share goals, the major ag equipment manufacturers are utilizing their leverage to achieve their aim of fewer but larger dealership groups. The approval or disapproval of dealer contracts has turned out to be the biggest hammer in their toolboxes.

"It's all about control of market share and purity within the stores," says Richard Miller of TriGreen Equipment, Murfreesboro, Tenn. "When awarding a new territory or market, it gives the majors the opportunity to exercise more control."

In compiling this report, Farm Equipment heard from dozens of dealers on both sides of the contract-transfer debate. While many were willing to go on the record with their views and comments, many more asked to remain anonymous. As one dealer put it, "Please do not use my name or reference my dealership as we are given such a hard time now, this could only make it worse."

The "Transfer" Issue

For the farm equipment dealer-principal, consolidation is becoming the single most critical factor re-defining the current and future landscape of equipment distribution in North America. Most recognize that it's a reality of the new marketplace — whether they like it or not.

More often than not, dealers say they understand the need for the majors to consolidate their distribution channels and, to some extent, their involvement in the transfer and sale of dealerships handling their equipment lines. It's how they're going about it that is pitting the "chosen ones" against those who find themselves on the outside looking in.

Those "chosen" by their suppliers to grow and expand their sales territories by acquiring other dealers say consolidation is necessary to eliminate in-line competition. The "outsiders" believe that limiting potential buyers to only the "chosen ones" also limits their ability to get fair value for the businesses they've spent decades — sometimes generations — building.

John Deere dealers were most vocal in both their criticism and praise of their major supplier in the ongoing contract transfer debate, but surprisingly, Kubota Tractor Co. wasn't far behind.

One frustrated Midwest dealer summed up the situation the outsiders find themselves in: "It's not fair the way the majors determine who is going to be the buyer of your business. I accept the fact that your major probably has to be involved in a business transition, but in no way should their involvement cost you money. There are many examples of Deere deciding who will be able to buy your business and how much you're going to receive for it."

In many cases, even if a dealer finds a capable buyer outside the ranks of those chosen by the supplier, the manufacturer can nix the deal, leaving the seller no where to go. "Can you imagine how that reduces the value of the business?" he asks. "Depending on his manufacturer, there isn't a damn thing he can do."

Why Consolidate?

While not all dealers see the need to reduce the overall numbers of retailers selling farm machinery, most believe it's a cost-cutting measure by the majors. "As far as I can see, their number-one objective is to decrease the costs related to supporting many owners or owner groups," says James Taylor, Hillsboro Equipment in Hillsboro, Wis.

"Ultimately, by consolidating, the majors are trying to minimize the number of owners they have to deal with, helping them reduce the number of field employees and division supervisors they have to employ," adds Duane Wallin of Colorado Equipment LLC, Greeley, Colo.

Mike Loscheider of Waconia Farm Supply, Waconia, Minn., doesn't currently carry a major line, but he'd like to. "I have tried to pick up a major line and was told in no uncertain terms that they do not want more owners, they want fewer owners so they don't have to deal with as many dealer groups. What they're really doing is eliminating competition."

But one dealer who requested anonymity believes that the major's reasons for fewer dealer-principals goes beyond the costs of working with a large network of retailers. They want company stores without having company stores, he says.

"They want to own the distribution channel without having the expense of brick and mortar or operational expenses. They want to control it all the way. They use contract approvals as a 'carrot' and dangle it in front of you to get other non-value things accomplished."

Fewer But Bigger

With John Deere leading the way, the unmistakable vision of the major ag equipment manufacturers is to have far fewer retailers peddling their colors in the future. It may or may not take the form of fewer overall locations, but it will surely involve far fewer but larger ownership groups.

Many smaller dealers say they feel the pressure to get out of the business and turn it over to larger area dealers long before they'd like to.

"Dealer programs and incentives have been redesigned to favor the larger dealers," says Leland Epting of Epting Turf & Tractor, Clinton, S.C. "Larger dealers can sell at a much lower price if they want to, and this is forcing the smaller dealers out."

As some argue that it's a mistake to reduce overall number of farm equipment retail outlets, others say that the emergence of much larger farming operations with fewer operators doesn't require having an equipment dealer located on every country corner anymore. The thinking is that it will take bigger dealers with more financial resources and talent to serve the growing and more demanding needs of the increasingly sophisticated and financially astute farmer.

Greg Hamilton, Hamilton Farm Equipment of Okanogan Wash., sees the move toward fewer and larger dealerships as inevitable, citing the growth of the mega chain retailers Wal-Mart, Home Depot and Walgreens as examples. At the same time, he believes there's more than a little irony in how they're going about it.

"There is definitely a trend toward 'the bigger the better.' The mom-and-pop grocery stores are already gone and many small hardware stores and pharmacies are going. So I'm not sure that we can expect farm equipment dealers to be exempt from this movement toward economies of scale.

"I wonder though, why our manufacturer, John Deere, thinks we should be able to compete against Home Depot and Lowes for lawn mower sales based on our better knowledge and personalized service on the one hand, but then force us into a larger and less personalized multi-store, multi-geographical situation on the other hand.

"Even though I'm not in favor of their methods, I can't argue that the current trend in most industries to consolidate in an effort to drive costs down through economies of scale is an incorrect strategy," Hamilton says. "Customers want service and competitive prices. I hope there will still be a place for a well-run, relatively small, local farm equipment dealership, but I'm not sure that market forces will allow it."

Philip Brooks, Brooks Sales, Monroe, N.C., believes that the aim of the consolidation efforts is to create both larger dealer groups and additional outlets, while leaving smaller dealers with nowhere to turn.

"They are telling the selling dealers that they can only sell to certain owners, which means the seller cannot get a fair price for his business. The buyer knows he can force the sale at a lower price because they are the only one the manufacturer will approve. This is giving the manufacturer the ability to consolidate and control markets without having to deal with as many individuals as when most dealerships were single locations. They want to have fewer dealer principals but more locations," he says.

Selling Your Dealership

Are you thinking about selling your dealership, or handing it off to a family member, in the next 3 to 5 years?

Nearly half of dealers surveyed told Farm Equipment they'd consider selling their businesses in the next 3-5 years.

Transfer & Fairness

For many dealers caught in the consolidation squeeze, whether the trend toward fewer dealer-principals is inevitable or necessary isn't the issue. It's the arbitrary nature of how it's being forced on dealerships, many who say they've served their suppliers well for decades and deserve the opportunity to sell their business for as much as they can get.

Many of these dealers believe the aggressive stance the major equipment manufacturers have taken in determining who they'll transfer retail contracts to is severely limiting their prospects and value of the businesses they've built. It's a fairness issue, they say.

As one dealer from the Northwest describes it, "One buyer is no buyer. It's pure 'restraint of trade.'"

"It's absolutely unfair," says David Bader, Bader Bros. Inc. of Reese, Mich. "The selling dealer has no options because the major determines who you can talk to. It might be only one possible buyer, and if he chooses to low-ball the price or worse yet show no interest, the selling dealer is screwed."

Another dealer, who requested anonymity, aimed his criticism directly at his major supplier's "system" for approving contract transfers only to nearby dealers that it has chosen. This leaves him with no recourse and no way to plan for his own future.

"The system used by Deere restricts the buyer to a neighboring dealer," he says. "There is often only one potential buyer and the negotiating strength lies with him.

"After all, he doesn't have to buy your assets or even pay close to fair value. He can let you liquidate and then walk in with a clean slate and take over your market. What seems more unfair is that Deere can prevent you from even doing a transfer of more than 10% of outstanding stock. So essentially they prevent you from having any continuity plan."

He also finds his supplier's lack of on-the-record standards for contract transfers particularly disturbing. "I would prefer that the manufacturer have a set list of objective criteria or standards necessary to acquire a dealership. But Deere won't allow it because they are trying to force the dealers into a world that conforms to their vision. They have absolutely no loyalty to their dealer organization."

Other dealers find the lack of communication on contract transfer infuriating, leaving them in business limbo. "This business has been in the family for almost 60 years and we don't know if our manufacturer will let us sell or not. They won't even comment on this subject," says Houston Randolph, Randolph Farm Equipment Co., Carrollton, Mo.

For some dealers, the contract-transfer process all boils down to politics. Despite running a successful dealership for years and having qualified family members to pass the business onto, one Ohio dealer offers an emotional response to questions about where his business will eventually end up.

"It is sad that a person can spend such a large part of their lives dedicated to building a great business, develop a good customer base and sell a lot of iron for the major only to have it taken away. And they say 'it's just business, it's not personal.'

"The majors hold all the cards and deal them out based solely on company politics to meet their objectives. Performance of a dealership seems to have nothing to do with approval of succession plans or acquisitions.

"Our store is very successful with excellent operating numbers at or above branch average for 'Dealer of Tomorrow' metrics. Yet, we've been told who we can sell to and that has been the only option offered."

He suggests that the best thing a dealer can do in this environment is to run his business to maximize his benefits and not worry about all the roadblocks put up by the supplier.

"The value of a business today is simply assets minus liabilities. Because the contract is so hard to pass on, there is virtually no value to the organization or customer following."

Looking at the bigger picture, he adds that he's come to believe that the major's real objective is to create dealers so large that they'll be unable to sell when they want to retire. "You may see a lot of company stores before we're done."

Views from the Other Side

Clearly there are two sides to the fairness of the contract transfer approval process. And in this case, it isn't only the manufacturers that view retail consolidation of the farm equipment business as necessary. Several dealers indicate that they not only share their manufacturer's views about contract transfers, but condone the process as well. Not only are they all for further shrinking of dealership numbers — for some, the faster the better.

Sam Lawson, Hartland Equipment Corp., Bowling Green, Ky., views the whole process as the cold, hard realty of doing business today. In his view, the manufacturers have every right to call the shots on who will sell their products and who won't. Furthermore, he's surprised that his fellow dealers are upset about how the business is shaking itself out.

"Because a new owner will be that company's representative and since the future of that company depends on who represents them, of course they should have the final say on who that person or entity will be," says Lawson. "To think otherwise is ridiculous.

"We all knew when we started in this business that this was the situation. We've all joked for years that we get what we make out of this type of business because we sell it for the sum of the assets at the end. Yes, it would be nice to sell to some zillionaire that would look at it as an investment opportunity but not know how to be a dealer. But why would that be fair to force that type of owner on to the manufacturer?"

For Lawson, the manufacturers' objectives in the contract approval process are abundantly clear. He says, he's not even sure why they're being criticized for trying to develop the best dealer network they can.

"I would think it is pretty clear what the manufacturers are trying to accomplish. They're looking for a dealer organization that is both financially capable of moving into the 21st century and has both the resources and the attitude that matches their long-term needs. I don't understand why this is demonized.

"A dealer without the scope to generate sufficient business volume will be unable to compete and offer their employees a career path or their customers the experience that they will demand as we move forward. "

Lawson offers his new $300,000-plus computer system as an example of the kind of resources dealers need to stay current in today's competitive marketplace. "I would hate to consider going forward without this tool," he says.

The Kentucky dealer also makes a point of strongly supporting his major supplier. "Not all dealers are in an adversarial position with their major. I happen to agree with most of what our major (John Deere) is doing and understand why they're doing it. To accomplish their vision, to protect their stockholders, to advance the company, to offer me future opportunities as a dealer, they have no choice."

The Way It Is

While Larry Straub of Straub International, Salina, Kan., sees the inherent unfairness of the major suppliers deciding who and who isn't a potential buyer, he says, he would likely do the same thing.

"It's probably not fair, but we have been the beneficiary when we've purchased stores. The same policy would probably hurt us some if we were in the market to sell. I don't like it, but I understand why they feel they need to control changes in dealerships," Straub says.

"This isn't 'bush league' anymore," he says. "You need professional dealers who know what they're doing. The manufacturer also needs to keep an eye on its long-range business objectives, and this will surely trend toward a lower number of dealer-principals with more locations."

On the other hand, Lance Carlson, Quincy Tractor LLC in Quincy, Ill., sees the current consolidation movement and contract approval process as an effective way of weeding out equipment retailers that are not performing.

"I know this is not what most dealer-principals want to hear, but after serving on our dealer council and seeing both sides of the fence, I believe there are a lot of instances where the equipment manufacturer is justified in getting involved," Carlson says.

"There are locations that are under performing and tying up franchises so they can concentrate on competitive brands. There are other locations that are just not good dealers at all, regardless of the brand."

From his perspective, Todd Niermeyer, Riesterer & Schnell, Antigo, Wis., believes consolidation is necessary to support the growing number of larger, more sophisticated farmers.

"We need to consolidate low-margin, low-performing dealers into larger more profitable dealer groups that can offer better product support and technology to the modern business farmer," he says. "This, in turn, enhances the farm's profitability and efficiency with uptime, lower-daily operating costs and productivity."

At the same time, Niermeyer believes consolidation should be "happening at a much quicker pace to eliminate in-line competition that's eroding profit margins."

Pressure to Get Out

Smaller equipment retailers say they're feeling the pressure to merge or make way for the dealers the manufacturer wants to expand.

According to one dealer who asked not to be quoted, equipment suppliers have programs like John Deere's Gold Star program where the company rewards dealers that qualify by meeting certain criteria.

He claims, "The company will bend the rules for some dealers to allow them additional dollars and discounts under the program. If the qualifying criteria were to be legitimately verified, there's no way some of the dealerships would pass."

Despite laws on the books in many states that forbid antitrust actions like prohibiting dealers from carrying other brands — better known as dealer purity — another dealer says manufacturers are finding ways around such prohibitions.

"The non-published 'dealer growth budget' programs has given some dealerships in my area $200,000 in settlement discounts that they don't give to other dealerships. This is determined by your alignment with the manufacturer, where you must not sell any competitive lines of equipment," he says.

Another dealer adds that someone needs to make sure that the manufacturers don't help the preferred dealerships take advantage of the high-performing smaller dealers by giving their favorites the unfair advantages such as target area programming and preferential retail programs.

"They're placing unfair demands on targeted dealers by increasing their market share and volume targets that don't mirror the manufacturers' own position in the market. These things are happening," he says.

"Dealer councils, state laws and dealer association involvement may help, but in the end, it comes down to unfair 'dealer agreements' that are interpreted as the manufacturer sees fit, depending on their plans for the individual dealer. Essentially, they can do whatever they want."

For another dealer, it's the arbitrary application of the dealer agreement and unreasonable roadblocks used by the manufacturers to hamper the process that is the real heart of the contract approval issue.

"We need published requirements for approving a dealer sale or a dealer buy-back and to have the requirements applied universally to all of the supplier's dealer group — as part of the dealer agreement. Today, the rules of engagement are made up 'as needed' by the manufacturers to meet the situation at hand."

No More 'Warm & Fuzzy'

The era of the handshake agreement faded into the past decades ago in the farm equipment business. But the current environment represents another major, even more significant departure in the relationship between manufacturer and retailer. Today, it seems, not even the paper on which dealer agreements are written offers much in the way of security for those expected to represent their suppliers well and sell a lot of iron.

Many in the industry continue to cite John Deere's CEO Bob Lane's comments in the now infamous interview with the Wall Street Journal in 2007 with sounding the death knell for the cozy relationship and level of mutual loyalty that dealers and manufacturers once enjoyed.

One dealer explains that he believes that manufacturers now look upon dealers as merely parts of their business. "If the part is broken, it will be replaced," he says, paraphrasing Lane's remarks.

"We all want that warm and fuzzy relationship that used to exist between dealers and manufacturers. Unfortunately, that's not in the cards. The best things dealers can do is to perform as well as they can in their market area, achieve a growing market share, pay their bills to the manufacturer and hope that they are considered one of the 'good parts.'"

While those dealers who believe they are one of the "good parts" and in alignment with their manufacturer see the future of ag equipment retailing as good and getting better, many more aren't sure what their future in the business holds. If they're not on their manufacturer's "chosen" list, they feel resentful and betrayed, with their very livelihoods in jeopardy. Others are uncertain and looking for answers that aren't forthcoming.

A long-time dealer sums up the dilemma confronting him and many of his colleagues today. "Manufacturers seem to make up the rules as they go to meet whatever objectives they are after. Dealers remain dots on the manufacturers' map. They set dealer standards of performance at levels they know only a small number of dealers can attain. But more importantly, they hold the hammer of being able to say 'yes or no' to the dealer's future."

Thinking About Selling? Advice from A Dealer Who's Been Through It All

Various studies show that the average age of a majority of farm equipment dealer-principles in North America is approaching 60 years old. So, it's not surprising that nearly half say they are considering selling their dealerships in the near future.

In fact, a poll conducted by Farm Equipment in May 2009, indicates that 46% of dealers are thinking about selling their dealerships — or handing them off to a family member, if they can — in the next 3-5 years. Another 28% said, "maybe, if the right deal comes along." The remaining 26% say they have no plans to sell their dealerships in the foreseeable future.

One dealer, who has sold two stores in the last 3 years, offers the following practical advice and suggestions to other dealers that may be looking to sell their business. He requested that neither his name nor location be used because he continues to own and manage two active farm equipment stores.

- Do your homework and get the dealership ready to sell at any time. "This may sound a little strange," he says, "but we believe that having a dealership ready and prepared to sell at any time creates a very lean and viable business model."

- Keep all inventories current. "The biggest hits will come in used equipment, parts inventory (obsolete, non-returnable-attachments and broken package quantities) and aged new equipment."

- Know and understand your state buy-back laws. "They may be better than what you will receive from the purchaser."

- Get two valuations. "We used the dealer association for one and a private company specializing in mergers and acquisitions. It cost about $4,000 each but was well worth it and was dead on. If the seller has not recently been involved in a buy-sell, this is probably more important in letting the seller know what to expect from the purchaser and the major."

- Prepare detailed schedules of all assets you plan to sell. "The list should include special tools, shop equipment, parts bins, furniture and fixtures, vehicles, etc. We listed replacement cost and arrived at a percentage for fair market value — usually 50-70%. This takes time to prepare but everyone should have these lists for insurance purposes and update them on an ongoing basis.

- Are you expecting "blue sky" or "business value?" "Even though majors tell you your business is worth something, they don't like to see their chosen buyer pay any great amount and preferably nothing. Some of this value may need to be moved to other assets in agreement with the buyer."

- Have the land and building appraised. "The contract approval steps allow the major to demand and accomplish most if not all of their goals. These usually include eliminating shortlines, forcing the use of selected business systems, signage and identification. They also involve utilizing their retail financing plans, setting strict market share objectives and future defined growth plans. Their approval system not only forces the purchaser to accomplish these in the prospective dealership, but also can be used to force the same objectives or others in some or all existing locations."

If Dealers Wrote the Contract

Like the debate about the fairness of the contract approval process, dealer's views vary on how they would change existing dealer contracts. But even those who side with their suppliers agree that existing contracts are largely one-sided and weighted heavily to the benefit of the manufacturer. "If you look at the personal guarantees, arbitration clauses and other mandates written into dealer contracts, there's no doubt they absolutely favor the manufacturer," says one Minnesota dealer.

"If dealers had the same army of lawyers dictating the same terms to the manufacturers, there's no way they'd sign such an agreement."

Asked what they would change about their contract, given the opportunity to tear it up and start over, dealers offer myriad suggestions.

One dealer said he'd prefer to have a franchise agreement vs. a standard dealer contract. "With a franchise, you actually earn equity in the brand you build and can sell it along with the assets of the business. With a dealer agreement, you don't have that."

But Alex Loewen of Deer Countryin Steinbach, Manitoba, says he doesn't want a franchise. "I want a contract, like the one I have with performance measurements and commitments from both parties," he says.

Overwhelmingly, dealers cite two specific changes they would make, depending on which side of the contract approval debate they stand.

Those who believe the current contract approval process is fair and equitable are looking for more protection of their sales territories. Those who say the current business transfer practice is patently unfair would include hard and fast stipulations for equipment buy backs, parts returns and written guidelines for selling or acquiring a dealership.

"I would want more protection from other inline dealers for my area of responsibility," says Sam Lawson of Hartland Equipment. "If I'm to be judged based on my market share within my AOR, then it should be judged against my other-brand competition and not my inline competition."

Larry Straub of Straub International agrees. "We would have more protected territories, with the volume going to the dealer who is assigned the territory. Or in the case of shared counties any dealer can sell in that county that has a portion of it, but outside dealers with no share of the county would give up their volume."

Richard Miller of TriGreen Equipment suggests that if the manufacturer wants to control who can buy a dealership and restricts existing dealers from selling to the highest bidder, the contract should contain mandatory buy-back provisions. He says that the supplier would need to guarantee current costs on parts, service tools and wholegoods, including freight and set ups.

But another, more pragmatic dealer, believes that the only way to accomplish anything when it comes to contract transfer, other than what the manufacturer stipulates in its dealer agreement, will be through passage of state laws that strictly forbid suppliers from unfairly restricting free dealings between a buyer and a seller if certain core requirements can be met.

"Otherwise," he says, "there is no way for a dealer today to be assured of full and fair value for his business."

Texas Dealer 'Stuck' with Two Majors

M&C Equipment of Brenham, Texas, is feeling the pain and ramifications of carrying both John Deere and Kubota tractor brands.

Mike Guthrie says, "I spent over 20 years building up my business to the point of being debt-free. What we had hoped and prayed for as our retirement is now in the hands of companies that have no regard for our future welfare."

Four years ago, he entered into an agreement to sell his dealership lock stock and barrel. All he would have walked away with, he says, were his personal artifacts and enough money to live the rest of his life and to leave his family financially secure.

At the time, all of his suppliers gave their approval, "even John Deere with a few strings attached, but they were acceptable. Kubota, on the other hand, killed the deal with the most absurd reasoning I have ever heard," says Guthrie.

"Today, I am being rewarded with Kubota trying to set up another dealer across the highway from me, less than 300 yards away. I have worked my fingers to the bone for these people and this is the support and thanks I get," he says.

Alabama Dealer Plans to Do It His Way

John Schaff, president of Foley Implement of Foley, Ala., has been a farm equipment dealer, selling the same brand for 42 years.

Now, 72 years old, Schaff says that he would like to pass his two dealerships on to his children. "But I was told, 'no can do.'"

Schaff says his supplier has encouraged him to merge with another dealer, but he's strongly against it. "We as a family are doing well profit-wise and I'm not going to take what we make and give it to other partners. We are going to keep our dealership as our own.

"Our family has agreed that when I die, they will turn the contract in if our supplier doesn't want to rewrite it with the family.

"I am a person who is not going to complain and we will continue to work in our own way because I always thought that family business was the American way," Schaff says. "John Deere has other plans, but we will continue to do a good job for them for as long as I live. I have always bled green," he says.

"As you may have guessed, I'm very upset."

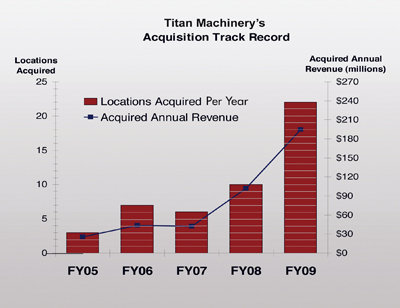

If the consolidation of farm equipment dealerships in North America is inevitable, the industry could use a few more white knights like Fargo, N.D.-based Titan Machinery.

Since 2002, when David Meyer and Peter Christianson merged their dealer operations to form Titan Machinery, the company has been in the forefront of the "unforced" side of dealer consolidation.

At that time, Meyer, chairman and CEO of the group, said that he and his partner saw "a wave of dealership consolidation" that was emerging as "the average age of the dealer-principal is getting up there. A lot of them are getting ready to retire," said Meyer.

At the time of their merger in 2002, the Titan group was made up of 10 Case IH and New Holland farm equipment locations. By the time the dealership was selected as Farm Equipment's 2006 Dealership of the Year, the Titan network had grown to 38 stores located throughout North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa.

With its most recent acquisition of Arthur Mercantile in Arthur, N.D., in May 2009, Titan Machinery's network of Case IH and New Holland farm equipment and construction dealerships reached 66 stores stretching across the Dakotas, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska and Wyoming.

Dealership groups like Titan Machinery, RDO, TriGreen, Birkey's Farm Store, Rocky Mountain Dealerships and others are providing retiring dealers a coveted alternative to the forced consolidation implemented by some major equipment manufacturers. (A list of the largest North American farm equipment dealership groups can be seen on Farm Equipment's web site at www.farm-equipment.com.)

Mixed Signals from Supplier Leaves Michigan Dealer Confused

"We wish we knew what they are trying to do," says David Bader, president of Bader Bros., a John Deere dealership in Reese, Mich. "They don't share their long-range strategy with us."

Bader relates some of his and other Michigan dealers' experiences that he says has left him bewildered and frustrated.

"I know that Kevin Godfrey in Jonesville Mich., had an agreement with Whelan's in Tecumseh, Mich., to purchase their dealership. Both buyer and seller were in agreement, but the territory manager from the Columbus branch disallowed the deal. "In 2009, Paul Bader from St. Louis, Mich., acquired that store, which gave him 6 locations.

"They keep preaching to us that 'if you're not a buyer, then you're a seller.' But when the Jonesville dealer tried to grow and buy out a single-store dealership, he found he wasn't on the 'chosen list.' It just doesn't make sense!

"Bader & Sons had to jump over the Jonesville location to acquire Tecumseh and they let it happen. I tried to add a fourth location in northern Michigan, 80 miles from the nearest Deere dealer, but they wouldn't allow me to do it. They said that I would be jumping over another dealer's territory. You see it works for some, but not for others.

"I've decided to take on Massey in my other store in order to grow. This is my livelihood."

Contract Approval: The 'Big Hammer' in Dealer Consolidation

Strategies for Dealing with Ownership Transfer Issues

Dealer Associations Get Into the Ring with the Majors