From the time he started Agri-Service, Cleve Buttars understood that to succeed, his business needed to be laser focused on people. First, it needed to be customer centric. That included delivering products and services to create customer satisfaction and loyalty. He wanted them to become advocates for his business.

In order to accomplish this, he also knew his employees needed to share this attitude toward the people walking through the dealership’s door. “One of the goals I set for my business was I would never work with or employ a jerk,” he says. “I was not going to work with somebody who was not a good person or who was difficult to work with. I planned on making my employees feel like partners because I knew how important it was.”

Dedication to this approach was based on Buttars’ 20-plus years of experience at his family’s farm equipment dealership, Buttars’ Tractor, in Logan, Utah. “I worked there from age 12 to 35. I even worked full time when I went to college. I started in the parts department and gradually went to sales and then management.”

He says that’s where his philosophy on how to run a successful dealership — focused on people, externally and internally — developed.

New Beginnings, Stiff Competition

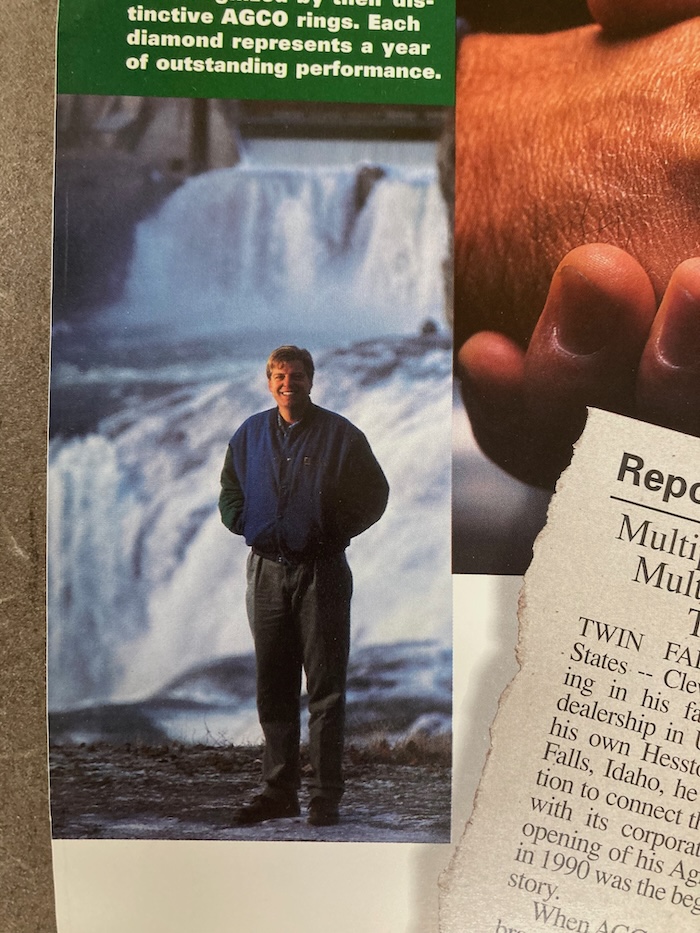

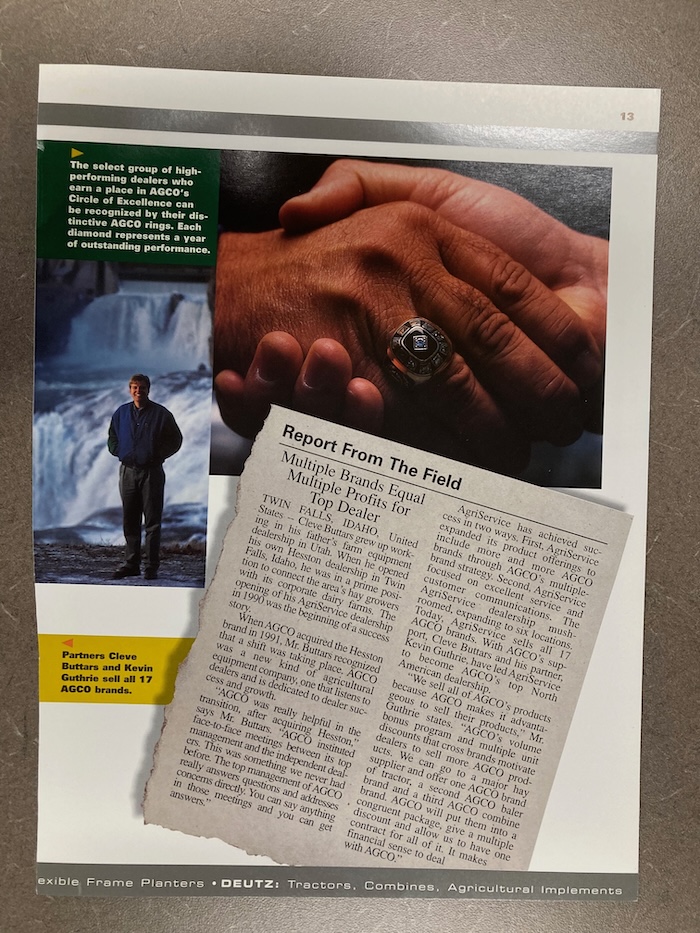

In the fall of 1989, at the age of 35, Buttars decided to strike out on his own and leave the family business. He was encouraged by Paul Rudge, district manager of Hesston at the time, to look at a failing dealership in Twin Falls, Idaho, some 200 miles away from Buttars’ Tractor.

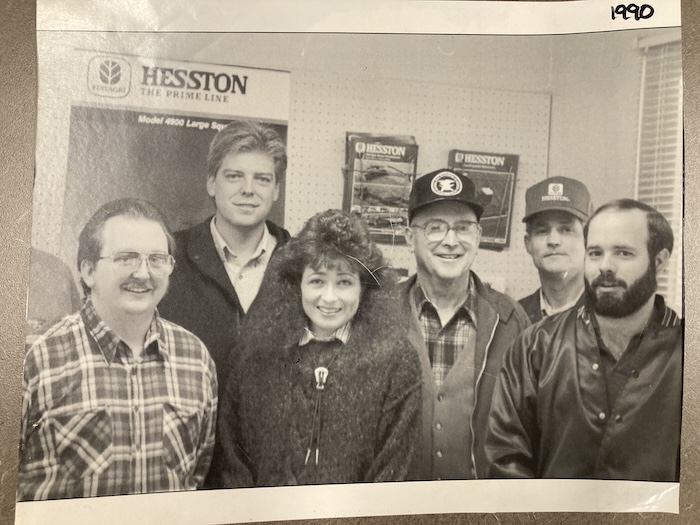

Rudge arranged an interview with Fiat Corp., which owned Hesston at the time. With some help from Fiat with start-up costs, Buttars hired another salesman and a parts person, eventually adding a service tech and a bookkeeper. He also invested $5,000 in “an old truck and some tools.”

In January 1990, Agri-Service was born as a Hesston dealership. Fourteen months later AGCO acquired Hesston, which at the time was in a 50/50 participation arrangement with Case IH. So, Buttars was not only stepping into the arena with established John Deere dealers, but he would also be selling the same Hesston big bale equipment as Case IH. The only difference was the Case IH balers were painted red.

“Other dealers in the west used Cleve as a sounding board when they wanted to discuss issues with AGCO or other dealership matters…” – Paul Rudge, former Hesston district manager

Despite this, Buttars admits his timing couldn’t have been better. During the 1980s, several large dairies from California moved their operations to the Twin Falls area and were switching from using small hay bales to big bales. According to Buttars, big balers produced better hay that held up better in bad weather and were simpler to transport, and Hesston dominated the big baler market through much of the country. “We lived and grew with the Hesston big balers from the start,” says Buttars.

“I came up there as a 35-year-old kid starting a new dealership that had to compete with established dealers. I knew we would get the sales, but I also knew that sales weren’t where dealerships make their real money,” he says. “For continuity, we needed to build our parts and service business. This is how Agri-Service would ultimately succeed.”

And he was right; the sales did come. After the first year, Agri-Service was among Hesston’s top 10 dealers. In the second year, it was the company’s third biggest and by the end of the fourth year in 1993, it topped all Hesston dealers in sales nationwide.

Nurturing Internal Partners

Asked to characterize what made him successful and what set him apart from competing dealers, Buttars explains: “I didn’t lose employees who we didn’t want to lose, and I didn’t lose customers who were worth keeping. I did whatever I had to do to hold onto them and developed a good base of employees and customers.”

Buttars paid his parts people and service techs “more than anybody else did. I knew that a competent parts person who would get up in the middle of the night and get customers the parts they needed was invaluable. The same thing for service. Techs who worked after hours could almost double their wages for overtime. I made it worth their while because it wasn’t me getting out of bed at 4 a.m. to help a customer.”

The dealership salesmen were paid fairly, but not as much as competing salesmen “because sales were easy,” he says. “We were selling big balers that everybody wanted. Tractors were a little trickier, but people came to us to buy those things, too.

“With our salespeople, we worked out a competitive markup. They had to quote the exact same price on new machinery and they made a standard commission that was livable. They made more if they bought the trade from the customer for less than I would allow them to put into the trade-in. If we allowed $18,000 for a used baler and they bought $16,000, they got one half of that windfall. That’s where they made their money. They became partners with me on that used equipment.”

Check out more from the Dealer Hall of Fame Class of 2024:

- Ronald D. Offutt, RDO Equipment, Fargo, N.D.

- Cleve Buttars, Agri-Service, Kimberly, Idaho

- Charlie Hoober, Hoober Inc., Intercourse, Pa.

- Paul Wallem, Wallem International, Belvidere, Ill, & Central Sands International, Plainfield, Wis.

- David Meyer and Peter Christianson, Titan Machinery, Fargo, N.D.

- Ferenc (1932-2017) & Tom Rosztoczy, Avondale, Ariz.

- Earl Livingston, Livingston Machinery (Parallel Ag), Chickasha, Okla.

- Orhan Yirmibesh, Badger Farm Store, Clinton & Avalon, Wis.

- Derek Stimson, Rocky Mountain Equipment, Calgary, Alta.

Nominate a Future Farm Equipment Dealer Hall of Famer

Submit a nomination for the next class! The Farm Equipment Dealer Hall of Fame recognizes the achievements of individuals who excelled in farm equipment dealer retail sales & service.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment